WASHINGTON, Nov. 2 (UPI) — As Americans face unprecedented challenges to voting amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the homeless community appears poised to cast tens of thousands of ballots this year, spurred by mobilization efforts and interest in the election, advocacy groups say.

An estimated 567,000 people experienced homelessness on any given night in 2019, according to the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s annual Point-in-Time count. Brendan O’Flaherty, a professor of economics at Columbia University, predicted that this number could be as much as 45% higher due to the pandemic, an addition of nearly 250,000 people.

Studies have shown that an average of 60% of the homeless population are eligible voters, which would add up to about 340,000 to 490,000 people given the estimated increase this year.

Many leaders who work with the homeless said they have helped larger numbers register, get ballots or vote early than in the past.

Nan Roman, president and CEO of the National Alliance to End Homelessness, heads the organization’s national Every One Votes campaign encouraging groups working with the homeless to incorporate voting into their efforts.

Roman said she doesn’t have data on how many homeless people have cast votes so far this year, “But…the feedback has been really good. And I think we’ve got…a lot more people…We’ve pushed it harder this year.”

‘I have to participate’

Christina Giles, a 41-year-old D.C. native experiencing homelessness, cast her ballot through early voting last week for the first time in years.

“I have to participate in the politics to stop things from happening,” Giles said, referring to injustices toward the Black community. A student at Strayer University, she said she has always been interested in politics and activism, but that she made sure to vote this year because she believes much is at stake.

The voting rate among the homeless population is historically one of the lowest in the nation. Just 41% of eligible voters who earn less than $10,000 a year voted in 2016 — the lowest of any income group, according to the Census Bureau. A 2012 study by the National Coalition for the Homeless found that voters experiencing homelessness are estimated to vote only about 10% of the time compared with an average of 54% nationally.

Although a series of court cases in the 1980s confirmed that the homeless could not be denied the right to vote for lacking a traditional residence, each state maintains its own requirements for establishing residency within a certain precinct. In D.C., homeless people can use the address of a shelter or social services provider to register by providing a government-issued document or a letter from a service provider attesting to the applicant’s living situation.

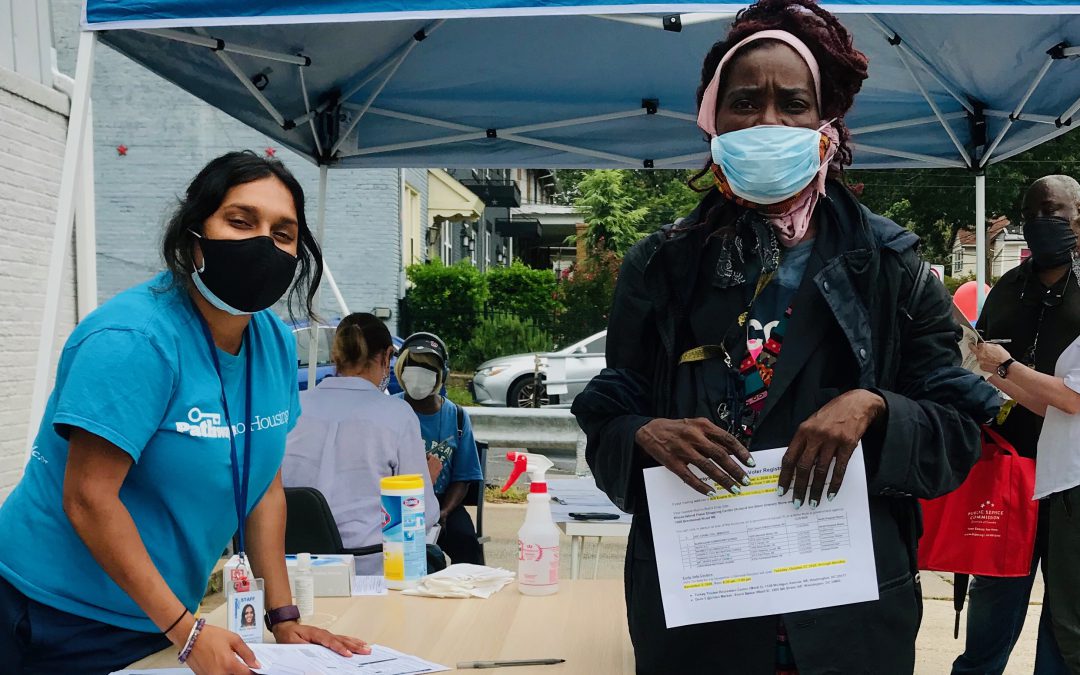

Giles said voting this year was “super easy” because she was homeless and eligible for many services, like voting assistance. She received help casting a ballot through Pathways to Housing D.C., a Housing First provider that launched a new get-out-the-vote campaign this year.

The initiative was formed after demonstrations that erupted this spring over systematic racism and inequality.

“That’s another misconception that a lot of people have about people experiencing homelessness — that they’re not interested,” said Briana Perez-Brennan, who heads the voting campaign at Pathways. She said that for many people, it comes down to being “recognized as a human being” and the realization that “my voice matters.”

“And that’s so huge,” she said. “Especially in the context of this election.”

Lack of address

Perez-Brennan said the group has registered more than 100 new voters.

Turnout for Tuesday’s election has beaten many records already, with a surge in early and mail-in-voting. Although most of the U.S. homeless population live in urban areas like New York City and Los Angeles, swing states like Arizona, Florida, Georgia and Pennsylvania had estimated pre-pandemic homeless populations of 10,000 to 30,000 on any given night in 2019, a range which could now be 14,500 to 43,500 due to the coronavirus. That could translate to thousands of homeless votes in states with razor- thin margins.

Homeless voters have always faced struggles casting a ballot because they lack an address, ID, transportation, Internet connections or access to other resources. This reality is made more difficult by some new anti-fraud voting laws like the Help America Vote Act, passed in 2002 to curtail voting irregularities seen during the 2000 election.

The law ultimately led to an intensification of residency and identification requirements in many states, two particularly difficult aspects of the voting process for the homeless who may not have an up-to-date ID or an address. Disenfranchisement of the disabled, immigrants and felons also disproportionately affects the homeless.

The pandemic has only complicated matters.

Many shelters have had to limit intake or shut down to meet safety guidelines, while the number of volunteers contributing time to shelters and programs like the voter campaign has decreased. Displacement between shelters is more common, as is breaking up informal encampments, making transport to the polls or mailing in ballots more difficult. And like other Americans, the homeless also face long lines, confusing instructions and COVID-19 fears if they go to polling places.

Maisha Pinkard, director of Friendship Place homeless shelter in D.C., said her team has recently helped register clients to vote and use the office as an address for their mail-in ballots or voter ID cards. Pinkard said more than 100 of her clients requested ballots; her group helped them get the ballots completed and in the mail.

Pathways plans to incorporate voter registration into its on-boarding processes permanently.”Now it’s a movement, it’s like a cultural thing,” Giles said about voting and protesting injustice within her community. She said she now is bringing up voting with others struggling with homelessness.

“Now I don’t have to be alone. There are people I can share it with and people I can talk to about it who are listening,” she said.