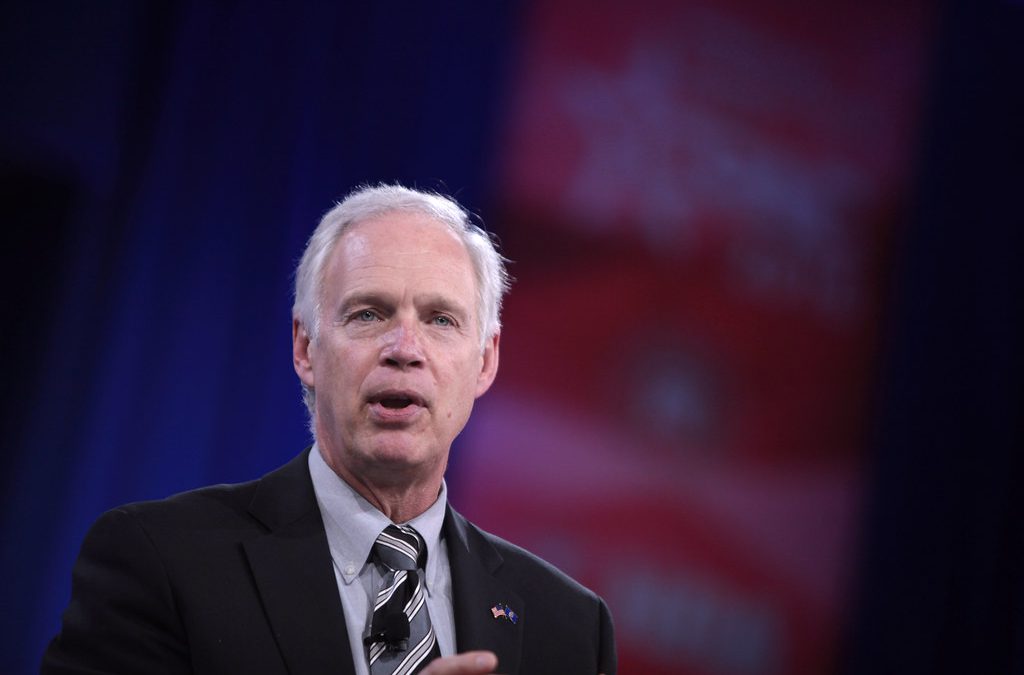

WASHINGTON — U.S. Sen. Ron Johnson is alleging Google targeted Get Out the Vote reminders on its homepage to liberal users in late October, saying it “could shift millions of votes,” but technology experts say the claim is not true.

Johnson, R-Oshkosh, and U.S. Sens. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, and Mike Lee, R-Utah, sent a letter to Google on Nov. 5 because big tech companies are not admitting the power and impact they have over Americans or “the threats they pose to our society, to our economy, to our freedoms,” Johnson said during a phone interview last week.

“But at a minimum, they have to admit, they can use or misuse their platforms, and they can have a dramatic impact on people’s preferences, and that includes election preferences as well, candidate preferences,” Johnson said.

While experts agree that Google and other companies gear content toward users, they say that Johnson’s allegations are unfounded.

Erik Nisbet, a professor of policy analysis and communication at Northwestern University and director of the School of Communication Center for Communication and Public Policy, said that claims of Google search manipulation are thinly veiled attempts to tarnish the election’s legitimacy.

“Republican Party and Republican leaders in Congress and Trump are trying to throw anything against a wall that might stick that might influence people’s beliefs that somehow the election was rigged, whether it was by Democrats, by tech companies, because of illegal voters and mailing ballots,” Nisbet said. “They’re just throwing anything and everything against the wall, to somehow tarnish people’s perceptions that this was a legitimate, free and fair election.”

Google CEO Sundar Pichai has not responded to the senators’ letter. Google has repeatedly denied allegations that its searches and algorithms disadvantage conservative users and content.

When asked during a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing if Google discriminates against conservative content, Google vice president of public policy and government affairs Karan Bhatia said, “No. We don’t factor political leanings into our algorithms at all.”

A study by the Pew Research Center analyzing if Americans believe social media censors political viewpoints revealed Republicans, and people who lean Republican, were about 1½ times more likely to disapprove of social media companies labeling posts from elected officials as inaccurate or misleading than Democrats or people who lean Democratic.

Johnson’s claims are rooted in research by Robert Epstein, a psychologist who studied arranged marriages and taught that couples could come to love each other. In 2012, Google put a security warning on his website, saying it contained malware; Epstein cried foul and eventually admitted the site had been hacked but said Google should have helped him with the problem instead of adding the label.

Siva Vaidhyanathan, a University of Virginia professor of media studies, director of the college’s Center for Media and Citizenship and the author of “The Googlization of Everything (and why we should worry),” described Epstein as “notoriously unqualified.”

“He has no training in the methodology it requires to make the claims he’s making. And his studies are consistently ridiculous. I’m familiar with this study, and it has no basis. Other social scientists have looked at it and have dismissed it quite easily,” Vaidhyanathan said.

Johnson said that the “overall concept” of Epstein’s work is “indisputable” because “the search is manipulative,” citing Google’s profits. Still, he said that Epstein’s research is open to challenges.

“When you’re presenting something like Robert Epstein is presenting, you’re gonna, you’re gonna have challenges,” Johnson said. “And truthfully, it’s open to challenge because he’s making assumptions and he’s making estimates. You can’t prove that it was switched, you can just, you just show this is how powerful manipulation is.”

In the run-up to the 2020 presidential election, several social media platforms introduced new measures to try to reduce misinformation. Twitter and Facebook banned political advertisements, and Twitter introduced a labeling system that flags tweets that it deems misleading.

Johnson and his Republican colleagues say the moves by social media companies ahead of the election ended up censoring conservative content.

“Who crowned Mr. (Mark) Zuckerberg, or Jack Dorsey or the CEO of Google, who crowned them the arbiters of truth?” Johnson asked, later adding, “There’s so many examples of Facebook and Twitter censoring just conservative ideas or conservative videos, you know, things that, you know, again, they’re the arbiters of truth.”

Tristan Harris, a former design ethicist for Google and the president and co-founder of the Center for Humane Technology, dispelled the idea that Google pushes content for any one party, saying echo chambers “can definitely exist on any automated platform” and Google pushes content it thinks users want to see.

Harris says that there is not evidence that conservative content is being censored by automated search algorithms such as Google’s and that it typically outperforms more liberal content on sites including Facebook.

“There’s a lot of accusations that people at the tech companies are biased in one direction or another, typically biased to the left-leaning,” Harris said. “There’s really no evidence when you let the machines do that, that there’s any bias toward one side or the other. If anything, conservatives are winning that battle, according to just the data.”

Harris said claims that tech companies consciously sway elections are untrue. Instead, their models prop up partisanship and echo chambers that have influenced voters for the last decade.

Vaidhyanathan, who described himself as “one of Google’s earliest and loudest critics,” said allegations that Google searches and interaction influence voter actions are an oversimplification.

“It’s a much more complicated process of thought and criticism and conversation with others. And that’s how we form opinions. We form opinions through a variety of interactions with people with institutions that with information, you know, and sometimes misinformation and disinformation. But it’s never simple,” Vaidhyanathan said. “And it’s dangerous to think that it is simple.”

Nisbet said that he is not as concerned about disinformation as he is with its long-term impact on the public’s trust in the democratic process.

“I’m more worried about misinformation, being more destructive into basically destroying people’s faith in democracy, democratic processes and adhering to democratic processes and valuing those processes,” Nisbet said. “The more people are dissatisfied with the procedure (of) democracy the less likely they’re going to value (it) as a form of government.”