In the months since George Floyd’s death on May 25, activists have taken to social media to organize and mobilize the ensuing racial justice movement like never before. Accessibility and immediacy of apps like Instagram and Twitter have enabled people to connect during a time when the nation has – literally – never been so distant.

This summer, social media propagated a new trend: crowdfunding and direct donations. What started as viral Venmo, CashApps and GoFundMe requests for financial support, became a way for Americans restricted by the pandemic to remain civically engaged.

There’s no obligation to donate, no tax write-off, no incentive and no required minimum. In June, Venmo tweeted in support of donating to Black Lives Matter. The company even credited some users $20 to pay forward to BLM campaigns.

But, as social media often does, this form of giving evoked questions around transparency. Giving is often based on trust and goodwill – markers that are difficult to judge virtually, on platforms that are inherently impersonal.

The Minnesota Freedom Fund (MFF), an organization that will pay the bail or bond for those who cannot afford it, received thousands of donations after George Floyd protests broke out in Minnesota, more than the small organization was equipped to handle. Their inability to allocate all of the funds ignited backlash and accusations of mishandling money. However, it became apparent that the organization was simply ill-prepared for such a sudden influx of cash and did not have the organizational framework to efficiently process it. MFF did not return a request for comment.

This distrust may be misplaced. According to individuals who have donated to or benefited from direct donations, it’s a legitimate form of activism and is very impactful.

Isabella Min, 21, a senior at Northwestern University, has been organizing crowdfunding campaigns for small businesses and organizations affected by racial injustice.

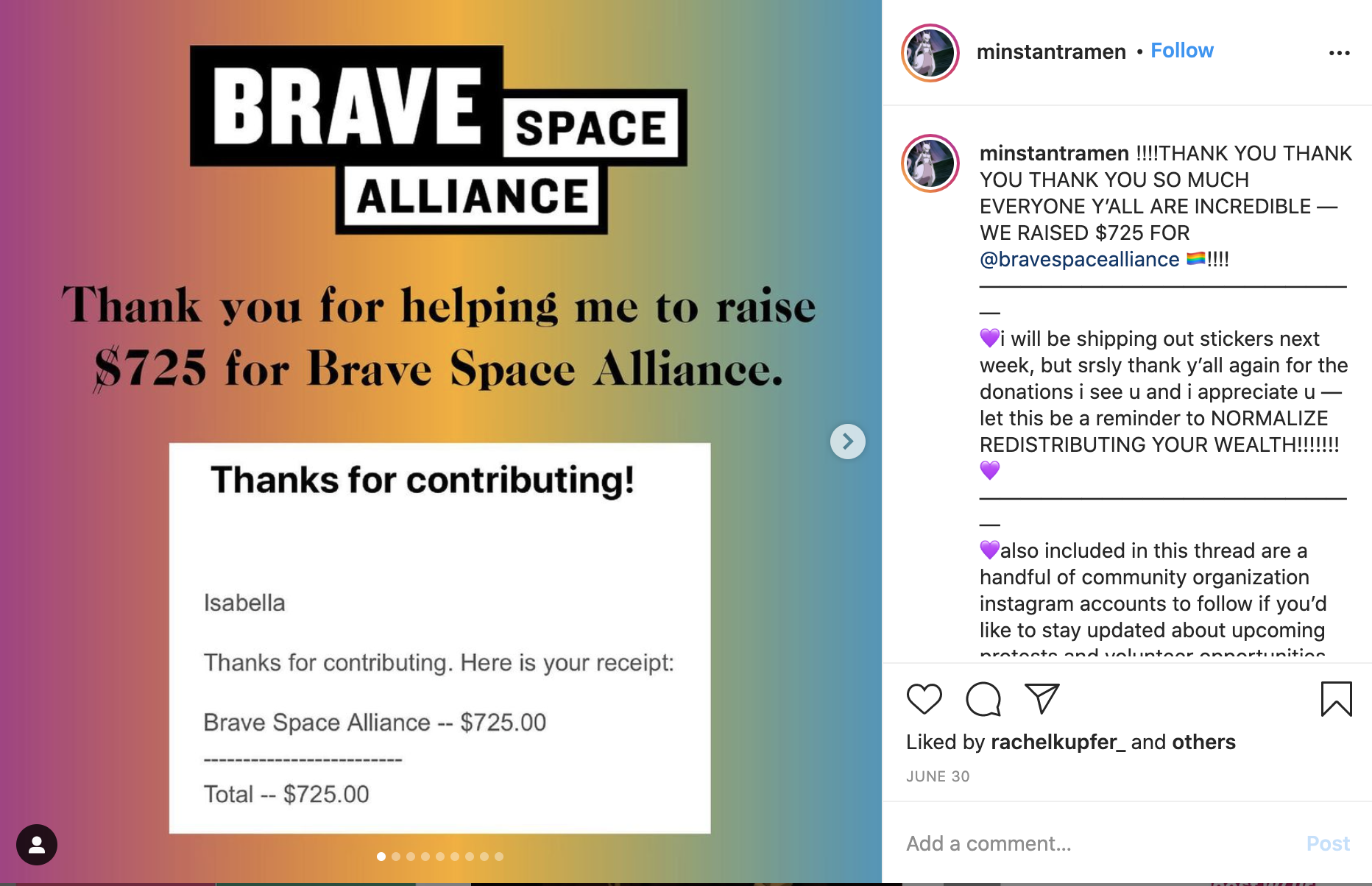

To quell potential questions of transparency, Min said that she publicly posts ‘receipts.’ These receipts are proof of where her contributors’ donations have been allocated. And, she is happy to provide further information if asked personally about where the donations are going. On her Instagram profile, she keeps a ‘highlight’ of all her past donations so that people can easily find them.

Now, five months after beginning these collective donations, Min said she is still steadily funding donations. She said an average donation is around $10, but one of her friends donates $100 to every fundraiser she organizes. Small, weekly or biweekly donations are much more sustainable for young people than the major financial contributions characteristic of bigger charities.

“One of the businesses we donated to was a small, Korean-owned business on the South Side of Chicago that faced damages after the first bout of looting back in June,” she recalled. “We ended up raising around $700. People I didn’t even know donated to it, and I knew it was something we could continue doing and continue to make an impact.”

One of the collective fundraisers Min shared on Instagram was for the Brave Space Alliance, a LGBTQ+ organization in Chicago. (Instagram: @minstantramen)

Direct donation requests began to populate social media feeds as Americans began to reckon with systemic racism. As many Black Americans shared personal experiences with racism, curated educational resources for their non-Black peers and engaged in countless conversations around race – there was motive to compensate their time and emotional labor.

As consciousness increased around the barriers Black Americans face, direct donations became an acknowledgement of the persistent economic disadvantages, improper historical remittance and continued systemic injustice. Conversations began to echo the debate around reparations.

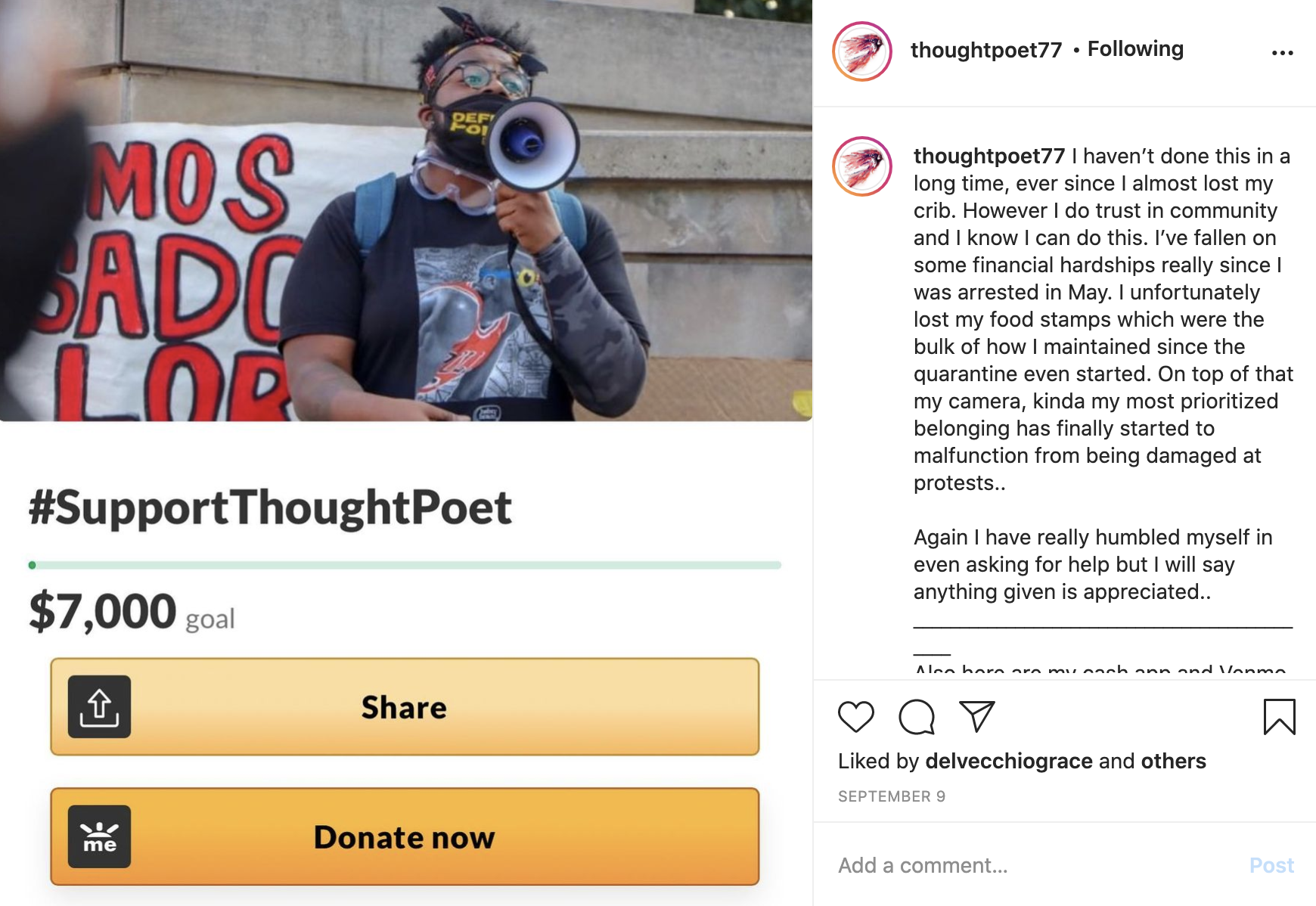

Twitter and Instagram were soon filled with what have been informally coined as, ‘fliers,’ for Venmo, CashApp and GoFundMe campaigns. Some were funds for victims or family members of those affected by police brutality, while others were setup for youth organizers whose leading role in organizing actions and protests this summer left them vulnerable to financial hardships.

Myndi Schmid, 34, a graduate student at DePaul University studying non-profit management, has made weekly direct donations since July.

Schmid has personally donated to “John Lewis State Street Mural (Rochester, NY),” a fund for a Black Chicago street artist who is making a John Lewis mural; “Help Black Trans Woman Survive Through Covid,” for a transgender woman and activist struggling as a result of the pandemic; “Mitchell Fire Relief Fund,” for a family in California whose home was ruined by wildfires; and “Save The Work,” a young Black photo journalist in Chicago whose equipment was destroyed – to name a few.

Another crowdfunding campaign on Instagram from a Chicago-based organizer facing financial troubles. (Instagram: @thoughtpoet77)

“It’s a different form of donating than what I’ve done in the past, which was more giving to larger nonprofit organizations,” Schmid said. “What I know is that large nonprofits do not need my $20 the same way someone facing eviction or someone who can’t make their car payment and needs a car for work, do. For these folks my $20 makes a much bigger impact than it does to those big organizations.”

Danielle Kilgo, PhD, a professor at the University of Minnesota who studies the media’s role in social and racial justice, said that this trend in digital activism is an innovative way to support a social movement.

“For the moms of victims [of police brutality], for the neighbors and the families who drop everything and take to the streets to demand justice – it takes sacrifice,” Kilgo explained. “When they receive some financial support, it makes it so they don’t have to give up their lives, too, in the fight for their lost loved ones.”

Kilgo also explained that direct donations humanize the sometimes transactional nature of larger charitable organizations. Direct donations are personal, measurable investments in the work an individual is doing. They have less of a tendency to be reallocated within a large bureaucratic entity, where donations can also fund operations and salaries.

Steven Morgan, 28, has been on the receiving end of direct donations. Morgan, who uses the non-binary pronouns they/them, said all of the donations they received helped to pay outstanding bills that had built up when their full-time job was severed during the pandemic. Morgan previously worked at Honeywell UOP, making oil and jet fuel for the Olympics. As a result of unemployment, they’ve also struggled with housing insecurity. Morgan has picked up part-time jobs with local nonprofits helping with organization and supply delivery, but it has not been enough.

At a press conference this summer for 18-year-old Miracle Boyd, whose teeth were knocked out by a police officer, Morgan (middle) and rapper Vic Mensa (left) came to Boyd’s aid when a reporter from NBC5 was accused of asking racially charged questions. (Madison Muller/MNS)

“I was really hesitant to make a request for money. First, it’s a pandemic and other people are suffering financially. I’m also someone who likes to make my own money,” Morgan said. “But, in a way, donating to a GoFundMe is like voting. It’s investing in what we want more of in our reality.”

That’s certainly been the case for 21-year-old Vashon Jordan Jr., a college student and independent photographer from Chicago’s West Pullman neighborhood, whose protest coverage went viral on social media this summer. While balancing his coursework at Columbia College, Jordan has covered almost every racial justice action in Chicago since late May. In July, he began receiving daily Venmo donations that have helped with his expenses like transportation and camera equipment.

“When people donate money, it makes them feel like they’re a part of something,” he explained. “When you invest in a person, and then see them doing things you appreciate, there’s a personal stake in their success. People are willing to do what it takes to support the work.”

Jordan recently published his first photography book, a collection of photos from this summer’s protests titled “Chicago Protests: A Joyful Revolution.” (Madison Muller/MNS)

Jordan said that he was at first uncomfortable asking for money, but people began requesting that he share his Venmo on Twitter so they could properly compensate him. The first time he personally asked for donations was on Aug. 9., after 20-year-old Latrell Allen was shot by police on Chicago’s South Side. News of the shooting spread quickly, and so did the false claim that police had shot an unarmed 15- year-old. On his way home from covering another event, Jordan happened upon the aftermath of Allen’s shooting. His photos, videos and interviews provided clarity and context to a situation rife with misinformation. When he later shared his rideshare cost for the day on Twitter, $76, he received nearly 40 times that in Venmo donations as a response.

“Journalists, organizers and activists are all doing very important work,” Jordan explained. “It’s a shame we are often the ones struggling the most financially. I know a lot of organizers are getting kicked out of their homes because their families aren’t comfortable with them protesting constantly during a pandemic. In Chicago, many Black and Latinx households are multi-generational and, thus, very vulnerable to Covid-19.”

As with any movement, there are the provocateurs who ask for donations in the name of a person or organization they are not affiliated with. But Kilgo said a much more pressing issue is the potential schism within an organization that could arise from personal funding.

“If an individual organizer, or organization is more social media savvy and becomes hyper funded, it could create tension within an organization or movement. Movements, historically, have always had infighting,” Kilgo said.

Without clear resolution, there are no plans for America’s racial justice movement to dissolve. But the coming months will determine if its momentum will be sustained by the bevy of micro donations that we’ve seen thus far.