WASHINGTON — Voting has always been a defining individual American liberty, but whether to exercise that right may, in fact, depend on other people.

Laura Ore, a 58-year-old nonvoter from Asheboro, North Carolina, said that she and all of her friends did not vote this year because they agreed that elections don’t affect their lives.

“Me and my friends don’t talk about politics much because politicians have no idea what’s going on in our lives,” said Ore in an interview. “You go ask either one of the presidential candidates how much a gallon of milk is, and they won’t know. They’re not going to be able to get food on the table for us.”

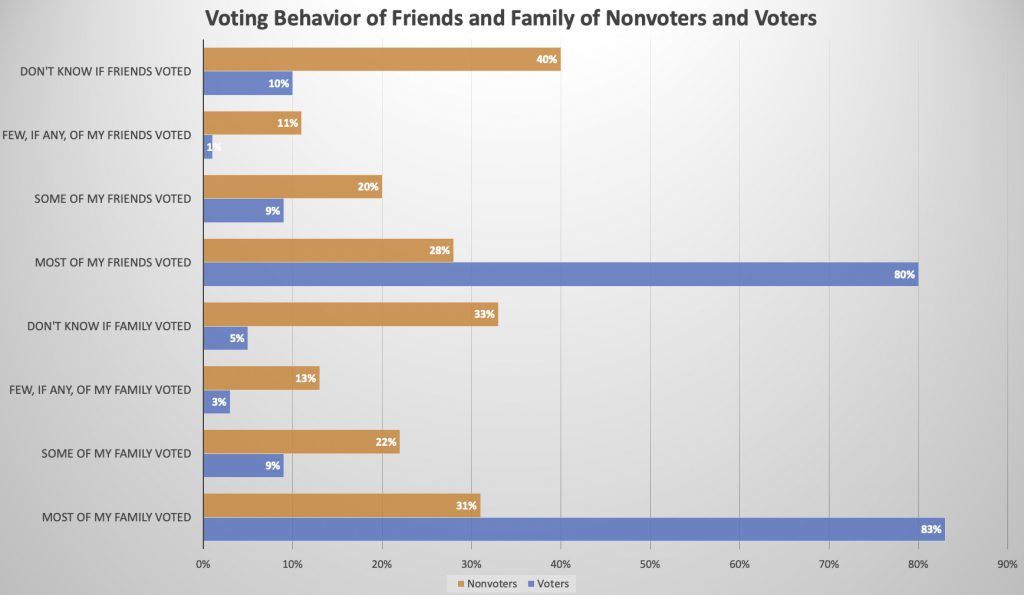

A recent Medill School of Journalism/NPR/Ipsos survey focusing on nonvoting behavior in the 2020 presidential election found that only about 30% of nonvoters surveyed said that most of their friends and family voted compared with around 80% of voters who said most of their friends and family also voted.

“We tend to think of voting as an individual act,” said John H. Aldrich, a political science professor at Duke University. “I make my decision, and I go to the polls. But in fact, it really is embedded in social connections like spouses and friends.”

Henry Wilson, a 41-year-old nonvoter from Houston who, like Ore, participated in the survey, has friends who are politically active, but their example didn’t push him to the polls on Election Day. Still, their action versus his inaction has left him a bit remorseful and second-guessing his nonvoting decision.

Data from the Medill School of Journalism/NPR/Ipsos 2020 nonvoter survey

According to Jon Krosnick, a professor of communication, political science and psychology at Stanford University, social conformity, especially with close family and friends, is one of the most powerful influences among the many conscious and subconscious factors that lead people to the polls — or keep them away.

“For a potential voter who is surrounded by lots of people who think voting is important, who talk a lot about politics, who are proud to wear that ‘I voted’ sticker, the natural thing to do is to conform,” said Krosnick. “And what social psychologists have known for 50 years is that conformity is a very powerful human tendency.”

Even just talking about politics with close friends and family may make it more likely for someone to vote. According to the Medill School of Journalism/NPR/Ipsos survey, a tiny fraction of nonvoters say they discuss politics with family every day; around 40% say they never discuss politics with their family, and around half say they never discuss politics with friends.

In situations where nonvoters are entrenched in politically apathetic communities, it might be more productive for activists to focus on changing the culture rather than focusing on individual people.

“There’s a lot more potential voters in groups that don’t vote very highly so you could invest in a community effort to reach them,” said Aldrich. “Working with community groups, like religious organizations, can help mobilize the whole bunch and make voting part of the culture.”

A community and culture that does value political participation can be a big motivation for potential voters. Marcus James, a 38-year-old Black voter from Alabama, said he felt obligated to vote because of his family and cultural roots.

“I voted because it’s my right, and I know the previous generations sacrificed their lives for me to be able to have that right,” said James. “They’re always in the back of my mind.”