WASHINGTON — When Washington, D.C.’s COVID-19 vaccination rollout began in December, Bread for the City, a nonprofit that provides health services to vulnerable and low-income communities, was one of the fortunate community health centers to receive a supply of the vaccine.

But they have been unable to vaccinate their patient population, which is predominantly Black, until now.

Dr. Randi Abramson, chief medical officer at Bread for the City, said the confusion began when the District opened vaccine appointments to anyone over the age of 65 as part of Phase 1B tier 1 on Jan. 11, without recognition of disparities amongst racial and socioeconomic groups within that age demographic.

“We saw our waiting room flip,” Dr. Abramson said. “We suddenly had all of these older white people, who are not our typical patient population, filling our waiting rooms.”

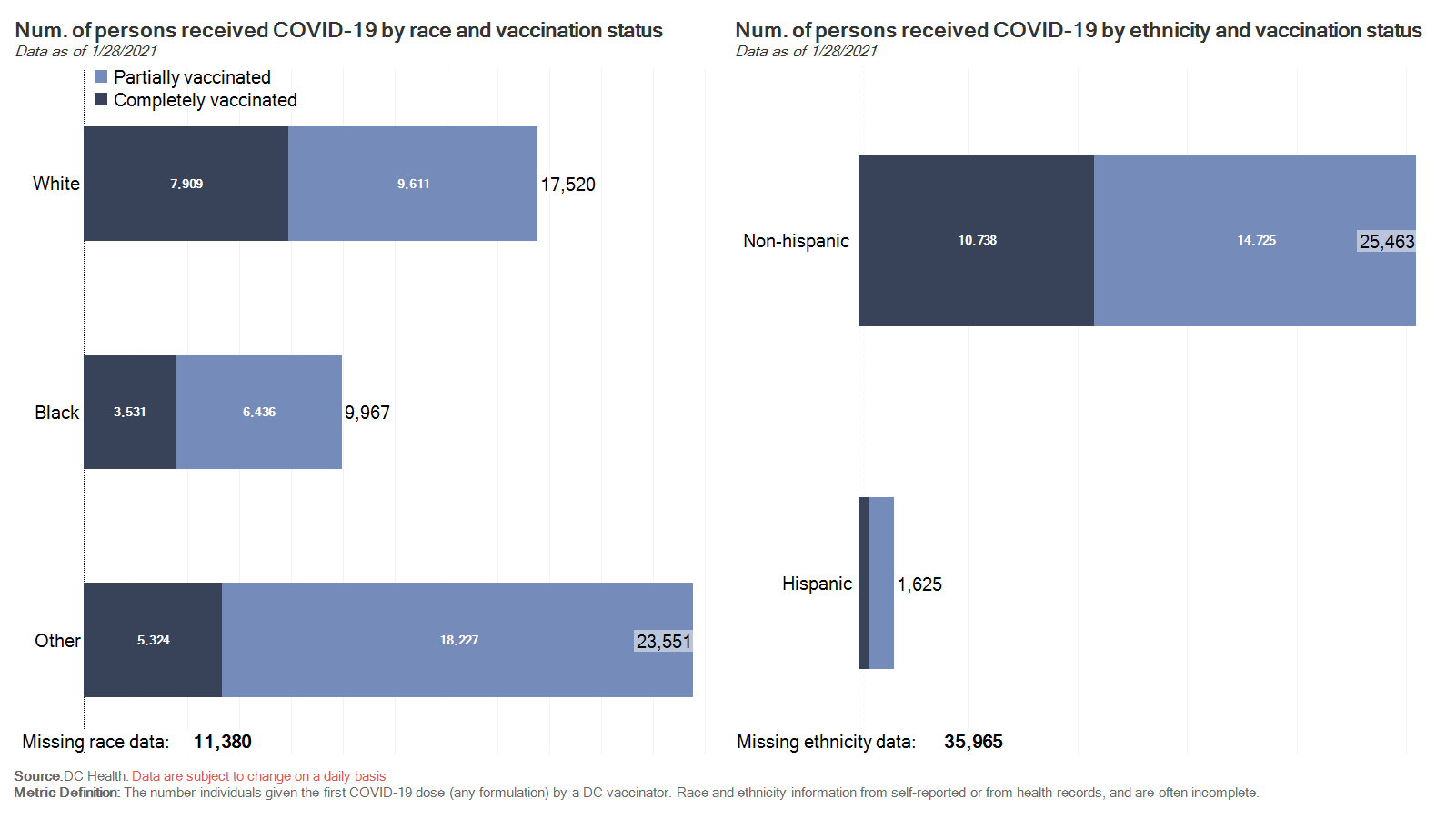

On Monday, the District of Columbia published COVID-19 vaccination data by race and ethnicity. The initial data, though incomplete, seems to support what Dr. Abramson saw in her waiting room: white Washingtonians are getting vaccinated at nearly two times the rate of Black residents.

Of the 7,000 appointments made available to people 65 and older, 40% were taken by residents of Ward 3, Washington’s wealthiest and whitest ward, despite it only accounting for 5% of the city’s COVID deaths.

Washington isn’t alone in seeing racial disparities in vaccine distribution. Of the 23 U.S. states that have published racial and ethnic vaccination data, all of them have reported white Americans are being vaccinated at rates of up to three times higher than Black Americans nationwide.

From the limited data, it is difficult to discern if any one factor is to blame for the racial disparities in early vaccination rollout. Decades of medical mistreatment have made it difficult for many people in the Black community to trust the vaccine. And, even with heightened outreach efforts, many Black Americans face structural barriers to information about COVID-19 and access to resources.

Dr. LaQuandra Nesbitt, the director of the District of Columbia Department of Health, warned people not to draw conclusions from the data because it is both incomplete and inconsistent.

DC Health vaccination data broken down by race and ethnicity as of Jan. 28, 2021. Source: DC Health

The data comes from the District’s centralized immunization system – which was recently updated to a new operating system – where healthcare workers are to record a patient’s age, gender, address, race and ethnicity. But race and ethnicity data is missing for tens of thousands of people, according to Nesbitt.

“If health care providers do not collect information on race and ethnicity … that data cannot be analyzed and provided to the public,” Nesbitt said during a press conference on Monday. “And that data, more importantly, cannot help to drive the District’s plan for a safe, effective and equitable immunization program.”

Dr. Abramson, chief medical officer at Bread for the City, said that while there have been “many missteps” in the District’s vaccine rollout she thinks they have been flexible and transparent about wanting it to work better.

When Bread for the City’s staff shared concerns about vaccine inequity with District officials, they were quick to respond. Last week, DC Health allowed them to close their health center to the general public in order to give their eligible patients, and eligible patients referred to them by other community organizations, the opportunity to get vaccinated.

The District also began prioritizing vaccination appointments by zip code in an effort to give preference to those who live in higher-risk, and disproportionately affected, communities like Wards 7 and 8.

Of the 175 vaccinations administered at Bread for the City last week, Dr. Abramson said only 17 were to white people. Many of her patients expressed hesitancy or fears about getting vaccinated, but Dr. Abramsom said she focused on validating patients’ feelings and answering any questions they had.

“If someone isn’t ready for the shot, that’s fine,” Dr. Abramson said. “I want to know how I can earn my patients’ trust. I think that’s really where we’re at.”

And while addressing racial disparities in vaccine distribution is essential, Dr. Abramson said she hopes that COVID-19 will force people to think about healthcare inequities and access to resources in the United States more broadly.

“We’ve got to do things differently going forward,” Abramson said.