WASHINGTON —With one week left in Black History Month, some scholars and activists say it’s time to change the way the subject is taught in schools, shining a light on systemic racism in addition to the often-taught subject of the Civil Rights Movement.

President Joe Biden has made it part of his mission to tackle racial discrimination following the murders of Black citizens and massive protests. On his Inauguration Day, Biden announced several executive orders aimed at addressing systemic racism.

Increased awareness of systemic racism has led to debate around the way American schools teach Black history. Just this month, a Utah school received backlash for suggesting Black History Month be optional.

For many students, Black History Month is their first exposure to any significant Black history and can serve as an important entry point to further discussion. Yet, according to CBS, there are no national standards for Black History Month curriculum.

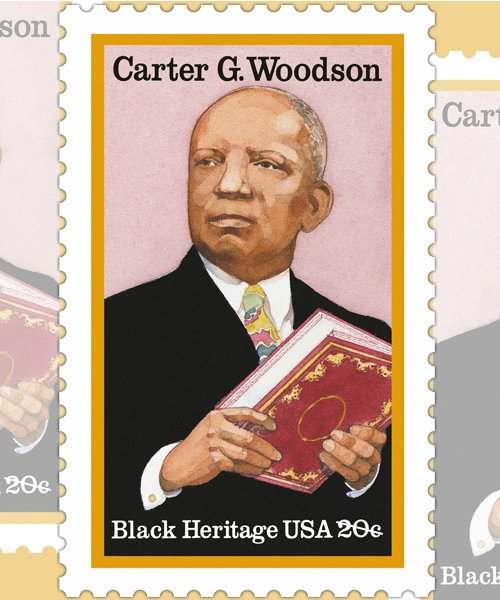

Black History Month, which started as a one-week celebration in 1926, was created by Carter G. Woodson to enlighten Americans on the accomplishments of Black Americans. The week became a month in order to incorporate a more inclusive history of Black people in America’s timeline.

“Black history is American history and American history is Black history,” said Faithe Norrell, the history services associate at the Black History Museum and Cultural Center of Virginia. “They are interchangeable. But too often, false narratives were taught, especially the Lost Cause narrative that came up following Reconstruction (and) during the beginning of Jim Crow.”

The Lost Cause Myth is a narrative created by Confederate sympathizers that falsely says the reason for the Civil War was Southerners’ concern for states’ rights, mainly secession, rather than their desire to continue enslaving Africans, and that enslaved peoples were happy and loyal to their masters, along with several other inaccurate statements, according to the American Battlefield Trust.

According to a 2017 American Civil Liberties Union survey, “Only 8 percent of high school seniors surveyed can identify slavery as the central cause of the Civil War.”

Meanwhile, a popular 2015 edition of a McGraw-Hill geography book still used in Texas, referred to enslaved peoples as “workers,” according to The American Scholar.

Amarah Alghadban majored in history at Chicago’s Saint Xavier University after taking classes at Moraine Valley Community College, just outside Chicago, where she remembers a professor telling the class that “some people” believe the Civil War was caused by the South’s desire to secede.

It wasn’t until she arrived at SXU that she learned the truth.

“My (professor) in American history in undergrad said, ‘Don’t let anybody tell you it wasn’t because of slavery. It was 100% because of slavery,’” Alghadban said.

Black history usually starts with a broad overview of slavery and the Civil War before ending with a discussion on the 1960s Civil Rights Movement, according to The Pew Charitable Trusts.

But while slavery remains a critical part of Black history, and American history, it doesn’t mean schools should start their Black History Month syllabi with it, according Richard Benson, a professor of education at Spelman College in Atlanta. He explained that the best starting point to begin teaching Black history is with the history of African civilizations.

In his class at Spelman, Benson takes his students back to Kemet, Nubia, Ethiopia, the empires of the Nile River and so on, working his way north toward Europe before reaching contemporary Granada, Spain. Doing so not only emphasizes that Black life existed before the “interruption” of American enslavement, but also the vast cultural differences across the world’s second largest continent.

“These persons were able to bury their dead, give praises to their ancestors, farm, create food, raise young,” said Benson.

For white educators in particular, to teach a comprehensive Black history curriculum, including enslavement, they have to have the courage to acknowledge white ancestors, in general, and the atrocities they committed, he said.

“The truth is uncomfortable,” said Benson.

Without this authentic learning experience, students are less likely to fully grasp the power dynamics of systemic racism and white supremacy that are still prevalent throughout American institutions, like health care and the criminal justice system, Benson and others say.

Brittney Henderson-Fiestas, a Black Lives Matter activist and doctoral candidate at University of Southern California, said students who aren’t given an accurate portrayal of Black history lack the critical analytical skills necessary to understand current events, like the Black Lives Matter movement.

“If you don’t have that education, the historical truth, when you look at liberation movements, and you hear people saying ‘Black Lives Matter,’ (you) won’t understand why Black lives are centered,” Henderson-Fiestas said.

If students are taught false narratives, such as the Lost Cause Myth, or only learn about historical benchmarks like MLK’s “I Have a Dream” speech, Benson said, the gravity of the past is minimized.

“You establish a perspective, based on misinformation, that now lends itself to the way that you see the descendants of an atrocity as not necessarily being the victims,” he said. “We begin to look at them as persons who are literally responsible for their own outcomes.”

This ideology drives many common criticisms heard today, such as in police shootings of unarmed Black people: “Why didn’t they just cooperate?”

But as the debate around how to teach Black history continues, and with it the current atmosphere of racial reckoning, a new question is raised as well: whether Black History Month remains the best way to educate students.

“We don’t need to be relegated to one month,” Norrell said. “We are the fabric of America. Black History Month is the kickoff point.”