Robert Cloutier, fifty-seven, has spent more than half of his life at Stateville Correctional Center in Joliet, Illinois. Incarcerated for nearly forty years, Cloutier has one of the more dangerous prison jobs during the pandemic: disposing of the prison’s biohazard waste. Since the onset of COVID-19 last March, this has meant collecting the facility’s used personal protective equipment (PPE).

At the start of the pandemic, Cloutier said he would fill several bags with discarded PPE such as gloves or facemasks. These days, he can make five stops around the prison and only pick up one or two gloves, and maybe a mask. “Whatever they are doing with biohazard waste—it ain’t in marked containers,” Cloutier said.

Everything he gathers goes into a room where used PPE has been amassing since the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic.

On March 24, 2020, the Illinois Department of Corrections reported its first confirmed cases of COVID-19 in three facilities: Stateville Correctional Center, Sheridan Correctional Center and North Lawndale Adult Transition Center. It wasn’t long before the coronavirus spread, killing nearly 100 people incarcerated in Illinois correctional facilities.

The Weekly sent incarcerated students in Northwestern University’s Prison Education Program at Stateville questions about their experiences during the pandemic and feelings about the vaccinations. Thirteen wrote back. All knew at least one person who had contracted the virus. Four who responded said they tested positive for COVID-19; four others experienced symptoms but were not tested at the time.

“I have seen people I laughed with behind these walls die within the last year because of this virus,” wrote thirty-five-year-old Benard McKinley.

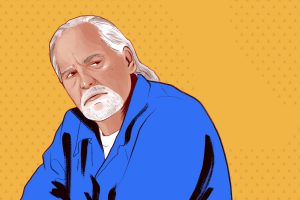

NPEP student Robert Cloutier (Shane Tolentino)

Incarcerated individuals are five and one-half times more likely to test positive for COVID-19 and three times more likely to die from it than the general public, according to the University of Chicago Law Review Online. Among the 1,091 inmates at Stateville, 303 have tested positive for coronavirus and at least thirteen have died.

In an effort to mitigate prison infection rates, Gov. J.B. Pritzker began granting clemencies in March 2020.

In January, Pritzker announced that corrections workers and incarcerated individuals would be included along with residents over sixty-five, first responders and education workers in Phase 1b of the state’s COVID-19 vaccine distribution plan, which began on January 25. The Illinois Department of Corrections began vaccinating prisoners in mid-February.

Despite receiving educational materials about the vaccine, distrust of prison officials and strained relationships with prison medical services complicate some the thirteen students’ feelings about getting vaccinated against COVID-19.

But while they are not entirely enthusiastic about the vaccine, they fear the alternative is worse.

“For me it’s not a matter of trust per say,” William La’Roy Peeples Jr., fifty-six, wrote in his response. “It is about me feeling safer taking it, than trapped behind steel and concrete with the virus running rampant and having zero protection from it.”

NPEP student William La’Roy Peeples (Shane Tolentino)

Cloutier said that until recently those who were showing symptoms were sent to an area of the prison known as F-House. That’s a problem, he said, because F-House was also where inmates who worked in Stateville’s kitchen, preparing food for the entire institution, were housed.

F-House was closed in 2016 because of health and safety concerns—none of which were rectified, according to the watchdog group John Howard Association of Illinois—but was reopened in May to house sick inmates.

“Initially they gave us disinfectant and bleach every day,” said Peeples. “But they soon stopped doing it, or when they did it was so diluted it had no real effect.”

Most troubling for some of the thirteen Stateville students is the risk prison staff pose. According to them, Stateville students, staff were not required to get tested for COVID-19 until January. And now, some are refusing to get vaccinated.

“I asked a female correctional officer today was she gonna take the vaccine if offered,” wrote McKinley. “She replied she had already turned it down.”

Stateville Correctional Center and IDOC did not respond to repeated requests for additional comment or information.

“By not adhering to their own rules proves my life is not their priority,” said forty-year-old LeShun Smith, “the staff brought the virus in.”

A recent study found that once COVID-19 enters an ICE detention facility, it can infect between seventy-two and ninety-nine percent of detainees within three months. While Illinois prisons may not be as crowded as detention facilities, the realities that inmates face are staggering. IDOC reported a statewide prison population of more than 29,000 inmates as of December 31, 2020. More than half of those incarcerated in Illinois are Black; racism has created systemic barriers to health care access and placed higher disease burdens on Black Americans, making them more susceptible to contracting, and dying, from the virus.

“Long before the pandemic, medical treatment in prison were way less than subpar,” Smith said. “Even after exposure they continue letting us fall by the wayside because we’re convicted criminals. They believe that our conviction nullifies our rights as U.S. citizens.”

NPEP student Benard McKinley (Shane Tolentino)

While prisons are required to provide medical care for incarcerated people, it is not unusual for incarcerated people to receive inadequate health care that has at times resulted in death. The problem is compounded by the fact that forty percent of incarcerated people have chronic health conditions.

Travis Dortch, fifty-three, who has Type 2 diabetes and hypertension, said he gets his medicine late, sometimes going weeks without it.

“I would complain—but my will and spirit is broken to just have the little I have,” he said.

Many prisons require requests to go to a medical unit be made in writing, which prison officials can take up to five days to respond to, according to the Prison Fellowship. Time is something those infected with COVID-19 do not have.

Broderick Hollins Sr., forty, was hospitalized for COVID in May before being moved to Stateville’s medical unit for twenty-seven days. He remains on medication as he recovers but said he still fears for his life.

Hollins wrote that nurses are among the only prison employees who enforce mask-wearing and that when inmates are tested for coronavirus, the nasal swabbing often is not done properly. But he remains hopeful that he will make it to his June 2022 parole date healthy, even though he believes prison officials consider inmates to be “just money, not humans with loved ones.”

While so many Americans struggled to adjust to the realities of life during the pandemic, for incarcerated Americans these realities were exacerbated by an uncompromising penal system.

Visitation with loved ones was suspended, according to Stateville’s website, access to technology was further limited and movement was almost nonexistent.

“For months and months, the facility didn’t prioritize my health and wellbeing,” Lynn Green, forty, wrote. “The facility functioned more like a disciplinary lockdown, than a quarantine. We were handcuffed everywhere we went and patted down by staff with the same gloves as they searched us.”

NPEP student Broderick Hollins (Shane Tolentino)

Isolation and inaccessibility to the few privileges usually afforded to those at Stateville are, for many of the thirteen students, the most unbearable aspects of the pandemic. And although mental health counselors have a weekly check-in with inmates, Dortch said it’s hard to open up to them.

“How can you tell someone who you know does not care if you live or die, about your mental problems,” Dortch wrote. He said efforts to distract himself are futile as he worries about the toll COVID-19 has on his loved ones. His mother has been hospitalized four times during this unprecedented time.

“I have become numb to the death of people daily—thinking I could be next,” he wrote.

“There is only hope in the unseen, which tomorrow brings the COVID-19 death toll with another thousand down—and I pray I’m not next. Keep me safe in the thoughts of the innocent until relief comes.”

Editors’ note: Instances of the word “inmate” have been removed or changed in this story in response to a request by NPEP.