When the COVID-19 pandemic erupted in Illinois a year ago, Gov. J.B. Pritzker instated a mandatory stay-at-home order. Now the state has more than 800 vaccination sites, and nearly 3 million residents have been vaccinated so far.

Even so, life in Illinois isn’t back to normal just yet. A mask mandate remains in place, schools and restaurants are operating at limited capacity and many are working virtually.

According to the Pew Research Center, 64% of adults working from home most of the time during the pandemic say their workplace is closed or unavailable to them. Thirty-six percent of adults working from home are choosing not to go to their workplace.

But for some first responders, the choice between going to work or staying home is difficult, weighing the responsibility to help others against the dangers that could bring to them and their families.

La Grange on-call firefighter-EMT Michael Murray worked through that decision last year by simply picking up fewer EMT shifts.

“Just like everything else that we do with the job … you’re never 100% guaranteed to stop everything bad from happening,” said Murray.

When the pandemic first hit Illinois last March, Murray said he was anxious about contracting the virus. He and the members of his department used copious amounts of hand sanitizer, wore masks and tried to keep as much space between each other as possible when on a call.

Now, Murray and his fellow emergency responders are less worried. They’ve learned how the virus transmits and even saw fellow teammates catch the virus and recover. And, he added, there was a level of fatigue that began to set in among the team as everyone remained on “constant vigilance.”

“I knew as long as I had my mask on and gloves and I wasn’t getting directly coughed on, I was probably pretty safe,” Murray said.

But he can still remember when he got the first call to see a COVID-positive patient.

“It’s a little bit like going to your first fire,” Murray recalled. “You kind of get in your wheels and your brain starts going a lot faster and you start jumping to things, back and forth.”

Before COVID, Murray would hop into his Honda Fit and drive to the location to meet the paramedics. He’d stand off to the side, ready to assist the paramedics the moment they asked. But, like jobs everywhere, coronavirus changed the way Murray worked.

Instead of heading straight to the site, Murray drove to the fire station. In the era of COVID, he takes a department vehicle instead of his own.

When he arrived at the COVID-positive patient’s home, he parked across the street. The officer responding to the call stood a few feet away, making sure everyone followed the new department protocols of social distancing, mask wearing and other safety measures. The officer even questioned whether the direction of the wind could carry the virus from the patient to the EMTs.

Murray could see one paramedic in full personal protective equipment — mask, gloves, gown. In an effort to minimize exposure, that paramedic was the only person to enter the house. Everyone else waited.

It was an exercise in patience, a fight against the instincts of every first responder.

“Everybody’s first reaction is, ‘Let’s help the paramedics, let’s help get the cart out of the ambulance, let’s get all the equipment inside,’” Murray said. “And once committed, especially that first call, everybody’s first instinct had to be stopped.”

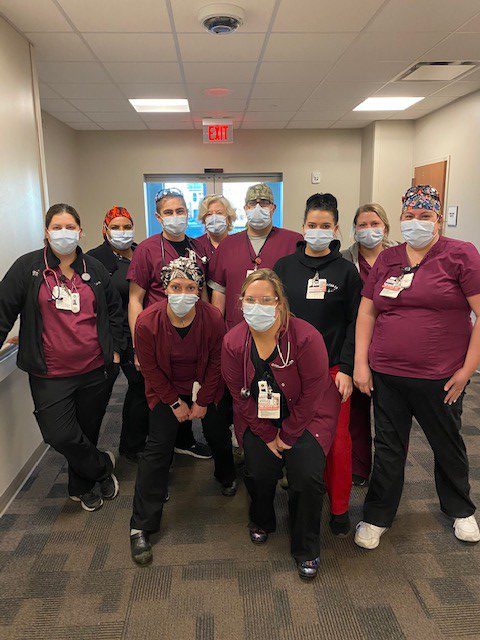

When it came to fighting instincts, Murray wasn’t alone. Fifteen miles away, on the South Side of Chicago at a tiny hospital in Portage Park, emergency room nurses fought their own first responder instincts.

Portage Park’s hospital is tiny, but it’s one of the busiest on Chicago’s South Side. It holds 30 beds, an immediate care center and an annex for short-term patients. All together, up to 40 patients can be admitted at one time. It’s a struggle in non-pandemic times. But with the onset of COVID, having a small emergency room ER created nightmare scenarios for those working there.

Like Murray, ER registered nurse Sara Tallman can clearly recall the first time COVID arrived at her workplace; it was late February 2020. She’d just finished her first year as an ER nurse and thought she had a handle on how things were run.

The day their ER had its first COVID patient, Tallman said, no one knew what to do. It was still early in the pandemic and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was still determining how to minimize transmission.

“We all ran to our lockers … to grab an N-95 (mask),” Tallman said. “We were like, ‘We don’t know what’s going on!’”

There was a debate on whether the nurses were safe with the patient confined to an isolation room. As days passed, and more COVID patients entered the ER, the debate became moot.

“We started putting up plastic coverings on the rooms that normally just have curtains because we started getting so many COVID patients that the (four) isolation rooms were filled,” Tallman remembered.

Adding to the stress, Tallman said the nurses were afraid that they didn’t have the proper protective gear.

When nurses are given PPE, normally masks are “fit-tested.” According to the CDC, fit testing ensures that the medical supplies, in this case masks, “forms a tight seal on the user’s face before it is used in the workplace.”

Tallman said the nurses ran low on fit-tested masks within the first few weeks of the pandemic; the hospital began rationing the remaining fit-tested masks, giving nurses one N-95 mask per week.

Tallman’s days were spent running from room to room as patients “coded,” or suffered cardiac arrests as their hearts went into overdrive.

“We were having, like, three codes at a time,” Tallman said. “(The patients’) hearts stop from all the difficulties with breathing.”

For a while, it was hard for Tallman to go into work, and even harder to leave, knowing that patients were being left behind to die.

“You’re leaving work defeated,” Tallman said solemnly.

As new information on the virus’s transmission came out with time, though, Tallman, like Murray, was able to relax slightly. Tallman and the other nurses aren’t as anxious now being in a room with a COVID patient.

She and Murray are focused on what Pritzker and Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot are doing to combat the spread of coronavirus.

“I thought initially (Pritzker and Lightfoot) were fantastic,” Murray said. “Especially because other than New York and Washington and a little bit of California, I thought we were the epicenter of what was going on. So I preferred to err greatly to the side of caution, and I think they did as well.”

When Pritzker lifted the stay-at-home order in July, the mask mandate remained in place. Some 250 people marched through Springfield to protest the governor’s orders.

“People just don’t know what’s good for them,” Tallman said. “They don’t see it because they’re not in the hospitals, so they don’t see the effect it’s taking on people. Someone can go downhill so quickly. It’s not like a flu. It’s not like anything I’ve seen before.”

Under Illinois’ vaccination plan, both Murray and Tallman have received the vaccine. Now, they’re looking forward to what the Biden administration will do to end the pandemic.