As a researcher at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, Miguel Chavez starts his days forming tissues from stem cells at 4 a.m. so he can get home in time for his virtual medical school interviews.

In the back of his mind, Chavez is terrified of infecting his family with the coronavirus. Of not having enough money to feed them. Of waiting longer to visit his father at the nursing home.

But another worry has plagued Chavez for much longer than the pandemic-related fears: Depending on the political climate, he could be deported from the country he’s known his whole life.

Chavez is among 29,000 health care workers who are in the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, according to the Center for American Progress, a left-leaning policy institute. Immigrant advocates at New American Economy and United We Dream said DACA health care workers like Chavez, who are often the main source of income for their families, long for a permanent status that would end the uncertainty and make them eligible for government assistance at a time when they are risking infecting themselves and their families with COVID-19.

“That’s really important for folks who are working on the frontlines of the pandemic to be able to have certainty that they’re able to stay and not have to simultaneously worry about the pandemic as well as their status expiring,” said Dan Wallace, deputy managing director at New American Economy, an immigration research and advocacy organization.

The House on Thursday passed a bill that would provide a pathway to citizenship for DACA recipients. If it also gains Senate approval, it would allow DACA recipients and other undocumented immigrants who arrived in the U.S. before age 18 to apply for a 10-year conditional permanent residency. To qualify, applicants would need to have earned a college degree or attended a bachelor’s program for two years, served in the military for two years or worked in the U.S. for three years.

“I’ve seen this happen many times so I don’t want to be too excited or feel as if something is going to happen,” Chavez said. “There’s been so many hopeful moments but then they lead nowhere. I am reserving my excitement until something concrete happens.”

Originally from Chorrillos, Peru, Chavez, 23, is one of nearly 700,000 “Dreamers” — unauthorized immigrants who came to the U.S. as children. Chavez has been able to study and work because of the DACA program created by President Barack Obama through an executive order in 2012, which grants recipients temporary permission to stay in the U.S. and temporary relief from deportation.

Former President Donald Trump took steps to terminate the program in 2017, but that effort was overturned by a 5-4 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in June that found, among other errors, the administration had failed to consider the hardship to DACA recipients.

Chavez said he lived in fear during the four years the DACA program was under challenge, and often found himself defending his immigration status because of what many critics have said was Trump’s anti-immigrant rhetoric.

On his first day as president, Joe Biden signed an executive order directing the secretary of the Department of Homeland Security to preserve DACA. A federal judge in Texas, however, could rule DACA unlawful in an upcoming case.

“That’s always on the back of our minds that the program can go away at any point because it is temporary,” said DACA recipient Juliana Macedo do Nascimento, policy manager at United We Dream, the largest youth-led immigrant network in the country. “We are scared because if we are the only breadwinners and working as essential workers but disposable at the same time, and then we lose our work permit, then our entire families will have to go without even the small help that we can provide.”

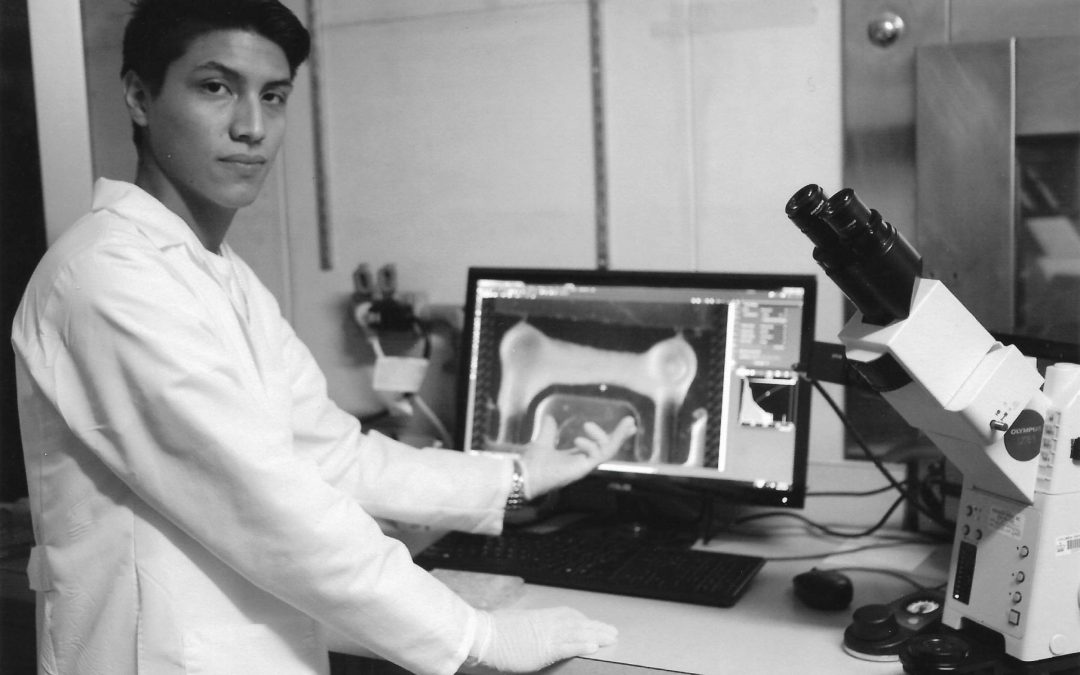

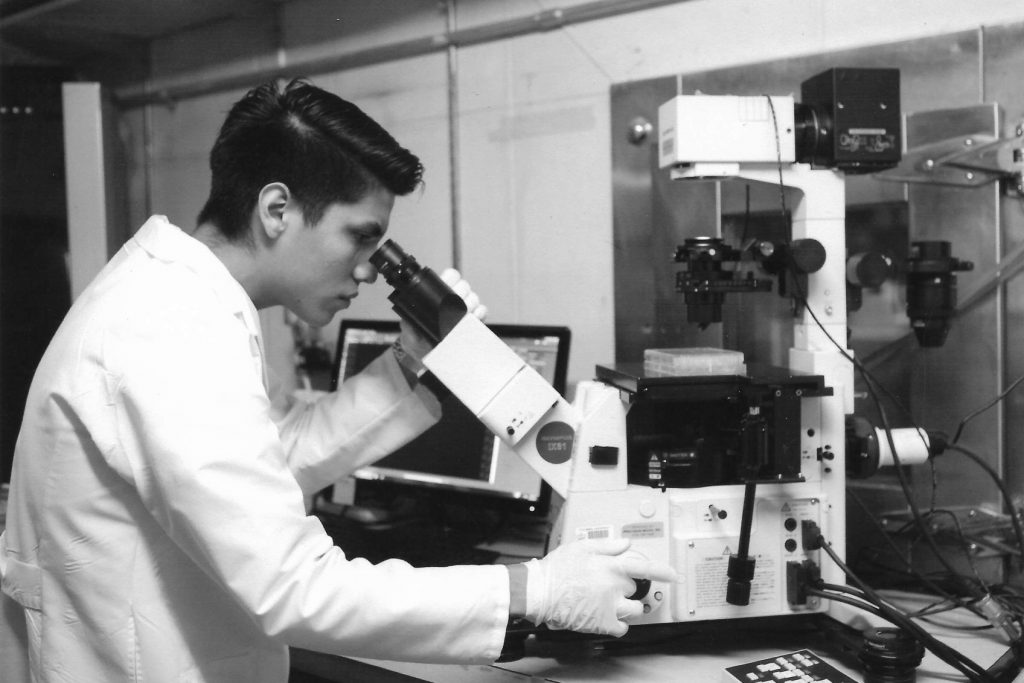

Miguel Chavez is at Columbia University Laboratory for Stem Cells and Tissue Engineering looking at newly transfected stem cells using fluorescent microscopy to verify whether his cells have been transformed. (Photo courtesy Miguel Chavez)

“A new life starting”

Chavez arrived in the U.S. in 2002 at age 4, when his family fled violence in Peru and settled in Port Chester.

His father, Edgardo, worked as a mechanic and his mother, Maria Isabel, as a housekeeper. But after overstaying their visas, the family was unable to file for green cards.

Chavez said he first realized he wasn’t like other kids in fourth grade when he was unable to apply to private school because he lacked proof of citizenship. Afterward, he was afraid that an U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement officer would find him.

In high school, Chavez didn’t know if he would be able to go to college until he applied for DACA status at 15, the minimum age to apply. It felt like a “new life starting.”

In June, he graduated with a degree in biochemistry from the City College of New York.

Chavez plans to renew his DACA status this summer. He hopes to win a scholarship covering the $500 renewal cost.

Miguel Chavez visits his father two weeks before the pandemic shut down nursing home visits. He was still recovering from his aortic dissection and two strokes he suffered in August 2019. Chavez tends to his father and assists him with physical therapy. (Photo courtesy Miguel Chavez)

“In prison”

In August 2019, Chavez’s father, who has a heart condition, suffered two strokes and was in a monthslong coma. Not eligible for health insurance, the family has paid part of his estimated $1 million medical bills through emergency Medicaid and charity care. Left paralyzed, he was moved to a nursing home, but Chavez said his father hasn’t completed the physical therapy he needs to recover.

Before the pandemic, Chavez visited his father daily after college classes, having long conversations with him while helping with his stretches and exercises.

The first time Chavez saw his father cry was on FaceTime, the only way they could communicate after COVID-19 shut down the nursing home to outsiders.

Chavez felt like he was “in prison.” He wanted to join racial justice protests but worried he would risk infecting his father, who he would take to medical appointments outside of the nursing home.

He became interested in medicine because his family’s inability to find accessible health care in Port Chester inspired him to want to help underserved communities.

He applied to medical school in June and was accepted to Harvard University, Cornell University, Columbia University, New York University and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Chavez hasn’t decided which medical school he’ll attend this summer, but he will remain in New York to be near his family.

But last September, his mother temporarily lost her housekeeping job, and she was ineligible for stimulus checks or unemployment benefits because of her undocumented status. Chavez picked up the slack, using his earnings as a researcher to provide for his mother and sister. Chavez recalls rationing food before the Salvation Army started delivering groceries to them.

“What the pandemic has done is just squeezed me more,” Chavez said. “It was crazy handling all these things at the same time.”

Miguel Chavez checks his stem cell cultures to see how they are, if there are any abnormalities or if they are too crowded and need to be split. (Photo courtesy Miguel Chavez)

“A nice end to a tumultuous journey”

If U.S. Senate Democrats cannot convince enough Republicans to vote for the American Dream and Promise Act of 2021, there are other measures that would provide legal residency for “Dreamers,” a term commonly used to refer to them due to repeated failed proposals in Congress that would provide similar protections for young immigrants.

Sen. Dick Durbin, D-Ill., proposed a bill that would allow undocumented immigrants who came to the U.S. as children to become lawful permanent residents if they pursued higher education, worked lawfully for at least three years or served in the military. It would also require them to pass background checks and pay an application fee, demonstrate English language proficiency and a knowledge of U.S. history, and have no history of felony convictions or other serious crimes.

Undocumented immigrants of any age would be given a path to citizenship through the U.S. Citizenship Act of 2021, which was introduced last month by Sen. Bob Menendez, D-N.J., and Rep. Linda Sanchez, D-Calif.

Chavez said that would give his parents the relief he felt when he received DACA status.

“It would be a nice end to a tumultuous journey,” he said.