To remotely teach her 5-year-old blind student how to navigate a new school this summer, Jennifer Freeman, an orientation and mobility in Escondido County, Calif., had to get creative. She made a large tactical map of the school, using raised bumps and lines to denote entry points, hallways, and other important physical landmarks, and sent it to the student’s home before meeting online.

“And she walked through with her hands!” Freeman said, recalling how she had watched excitedly as the student made progress toward a goal the seasoned teacher had thought would be impossible in a virtual environment. “That was probably my best lesson,” Freeman said.

Freeman has spent much of the past 14 months of the pandemic expanding her creativity for lesson-planning. While teaching during a pandemic has presented extraordinary challenges for all teachers, educators working with the visually impaired have had the especially difficult task of adapting a curriculum based largely on physical interactions—like teaching a student how to read braille by touch or how to walk with a cane—to the two-dimensional environment of online learning. Although technology plays a significant role in many special education programs for the blind and deaf, there’s little precedent for a completely virtual education for the visually impaired, and certainly no rule book.

“What COVID-19 has done for our field is to lay bare the biggest challenges and the biggest opportunities that the blindness education field faces,” said Mark Richert, interim executive director for the Association for Education and Rehabilitation of the Blind and Visually Impaired.

Jennifer Freeman, an orientation and mobility specialist in Escondido County, Calif., schools — Courtesy Photo

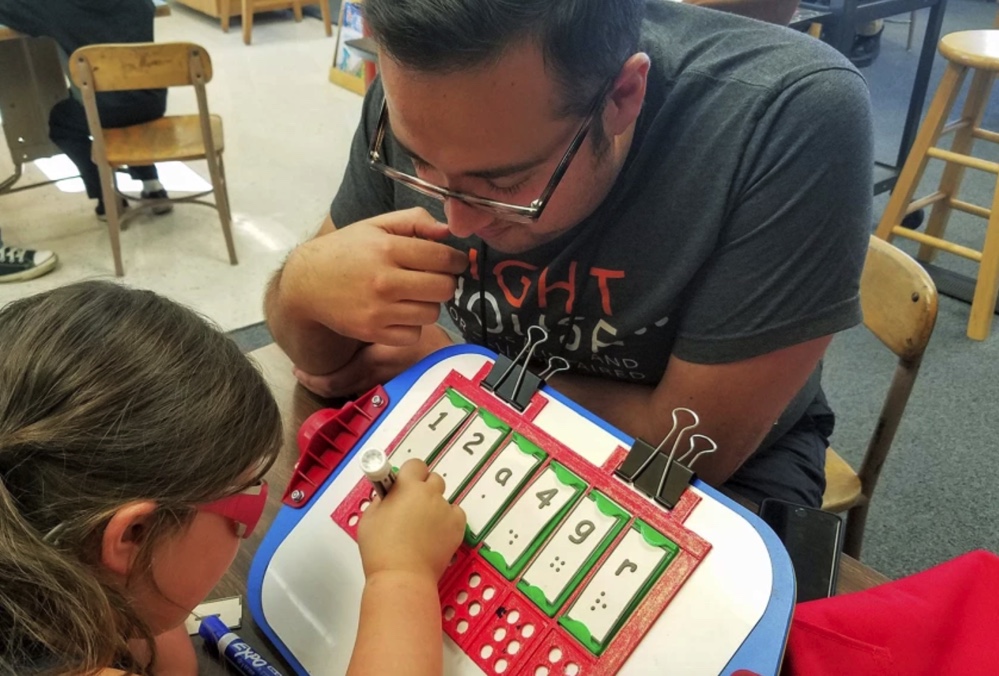

As an orientation and mobility specialist, Freeman works side by side with teachers of the visually impaired to help students learn basic daily living activities, like getting to and from school, and meet their academic requirements. She is part of a niche group of special education teachers who serve an estimated 60,000 students across the country, according to the American Printing House for the Blind, although some estimates put the number well above 100,000 students.

Like most educators across the country, Freeman and her colleagues had to adapt to pandemic teaching practically overnight.

As the only dedicated assistive technology specialist for the visually impaired in California’s Sonoma County, Neal McKenzie had to push to gain access to his office after his district shut down schools to curb the spread of the coronavirus early in 2020. He was given one hour to grab all the equipment he could carry, including heavy machines and supplies for making tactile and braille materials.

Since then, McKenzie has kept the machines running in his garage nonstop to produce what the county’s 120 visually impaired students need to keep up. On many days, he ends up working 12-hour shifts.

“The amount of support it takes to actually get them the materials that they need and they deserve—it’s a lot,” McKenzie said.

Pandemic fuels renewed push for federal support

Richert and other special education advocates are hoping that the difficulties and educational inequities laid bare by the pandemic will prompt more federal support for the needs of blind and visually impaired students. They have been lobbying Congress for more federal funding through the bipartisan Alice Cogswell and Anne Sullivan Macy Act, named after the first deaf student formally educated in the United States and Helen Keller’s renowned teacher. Originally introduced in Congress in 2015, the bill aims to make sure that children with visual or hearing impairments will be properly counted, evaluated, and supported.

Although they are protected under existing federal special education legislation, deaf, blind and deaf-blind students often fall through the cracks of the education system and receive fewer specialized services than they need—leading to lifelong learning problems or deficits that could have been prevented, according to Richert.According to the Census Bureau’s most recent American Community Survey , from 2019, about 7.5 million Americans consider themselves blind or have “serious difficulty seeing even when wearing glasses”— about 2.3 percent of the total population. But people with visual impairments make up just 1.2 percent of employed, working-age adults.

U.S. Sen. Ed Markey, D-Mass., and U.S. Rep. Matt Cartwright, D-Pa, introduced the Cogswell-Macy Act once again in the House and Senate simultaneously in March with co-sponsors from the Democratic and Republican parties. With both chambers under Democratic control for the first time in over a decade, proponents hope it has a better chance of becoming law. As of now, the bill is awaiting further discussion in congressional committees.

“We have seen during this pandemic just how challenging —and vital—it is to ensure that students receive the best education possible to help them develop, grow, and thrive,” Markey said in a statement announcing his legislative proposal. “The Alice Cogswell and Anne Sullivan Macy Act will improve access to personalized services and effective education for deaf, blind, and deaf-blind students across the nation.”

Under federal law, children with vision impairments have the right to receive an array of special education services aimed at maximizing their personal, academic, and professional potential from birth, or as soon as their vision issues are detected. Typical educational services include instruction on basic living skills, orientation and mobility training, and social skills.

The wide-reaching bill under consideration now would require states to more proactively identify students who need special services and better document strategic planning for each child’s development. The legislation would also intensify the Education Department’s monitoring and evaluation requirements along and seek to ensure the availability of qualified staff to work with these students.

Leslie Edmonds, a teacher of visually impaired students in Escondido County, Calif.

— Courtesy Photo

But educators who work with students who have visual disabilities also say some of the changes to normal instruction caused by the pandemic have proved beneficial. For one, teachers have been able to communicate with families in a more intimate way than in the past—gaining valuable insight into the student’s home life and sometimes engaging entire families in the lessons.

“We just have this lens into a person’s home now,” said Leslie Edmonds, a teacher of the visually impaired who works with McKenzie in California. “Sometimes, you see generations coming together through COVID-19, helping each other out and getting involved in the education of little ones or the kids in school. That might not have ever happened before.”

Edmonds and several other teachers of the visually impaired and orientation and mobility specialists said they will continue using some of the new technological tools and strategies they have learned as in-person teaching resumes.

“In some ways, COVID has shown what the advantages of doing things remotely can be,” Richert said, “and, of course, also exacerbated all of those same challenges that we’ve had.”