WASHINGTON — Democrats in Congress are pushing to abolish part of a New Deal-era labor law that allows businesses to pay workers with disabilities as little as a few dollars an hour, calling the practice outdated and discriminatory.

A bill in the U.S. House would immediately halt the issue of special certificates that exempt companies from paying the federal minimum wage to certain workers with disabilities. It would also phase out existing exemptions.

“Each person in this country deserves access to equal employment opportunity,” said Rep. Alma Adams, D-N.C., during a House hearing this week. “Yet one of our foundational labor laws, the Fair Labor Standards Act, still allows workers with disabilities to be paid less than their peers.”

Congress approved the far-reaching act in 1938 in an effort to strengthen the rights of workers and labor unions. The provision for those with disabilities was included to give businesses an incentive to hire them at a time when most were believed to be incapable of regular work.

John Anton (right) and his mother present testimony during the hearing to discuss subminimum wages for employees with disabilities. (Courtesy of House Committee on Eduction and Labor)

Some 40,000 employees with disabilities were being paid less than the federal minimum wage of $7.50 an hour as of April, U.S. Labor Department statistics show.

Some could be paid as little as $2.50 or even less, Adams said.

Democrats have sought for several years to revamp the section of the 1938 Act that applies to workers with disabilities. The bill appears to stand a good chance of passage with the party in control of the White House and Congress.

“Phasing out subminimum wages for workers with disabilities is fundamentally a civil rights issue,” said Rep. Suzanne Bonamici, D-Ore., chairwoman of a House panel with jurisdiction over the issue.

Some Republicans contended the proposal would give businesses less incentive to hire workers with disabilities.

“I think the injustice would be if we decreased the amount of people that we could get in those types of programs, and I think by eliminating this, that is what we’re doing. Or at least that’s what the facts tell us,” said Rep. Lisa McClain, R-Mich.

She argued a better approach would be to provide incentives to businesses to increase wages for people with disabilities rather than to mandate them.

Rylin Rodgers, director of public policy at the Association of University Centers on Disabilities, said the end of the wage exemption wouldn’t causes businesses hardship.

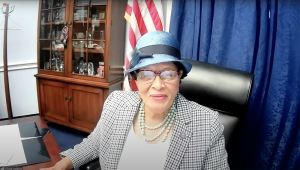

Rep. Alma Adams, D-N.C., chair of the Workforce Protections Subcommittee, introduces witnesses testimony at hearing about subminimum wages for employees with disabilities. (Courtesy of the House Committee on Education and Labor)

“The idea that it would be harmful for businesses is a really offensive argument because the idea that a business model is to make a profit on indentured servitude and paying people far below the market value for their labor is very un-American,” Rodgers said in an interview.

The proposal would give businesses that use the special wage exemption several years to adjust and partly subsidize an increase in pay for those with disabilities.

The bill would also create new options for workers with disabilities to get engaged in community work or volunteering, particularly those who may be unable to work a full day.

“Many people with disabilities will transition from receiving subminimum wage to working full-time in a competitive integrated employment,” Rodgers said. “But there are some individuals for whom their current situation, or their disability status, means that they’ll need a different blend.”