WASHINGTON — As Thursday’s government funding deadline approaches and the threat of a government shutdown looms over Washington, Senate Democrats and Republicans are exploring a unifying distraction from their budgetary standstill: the Britney Spears conservatorship case.

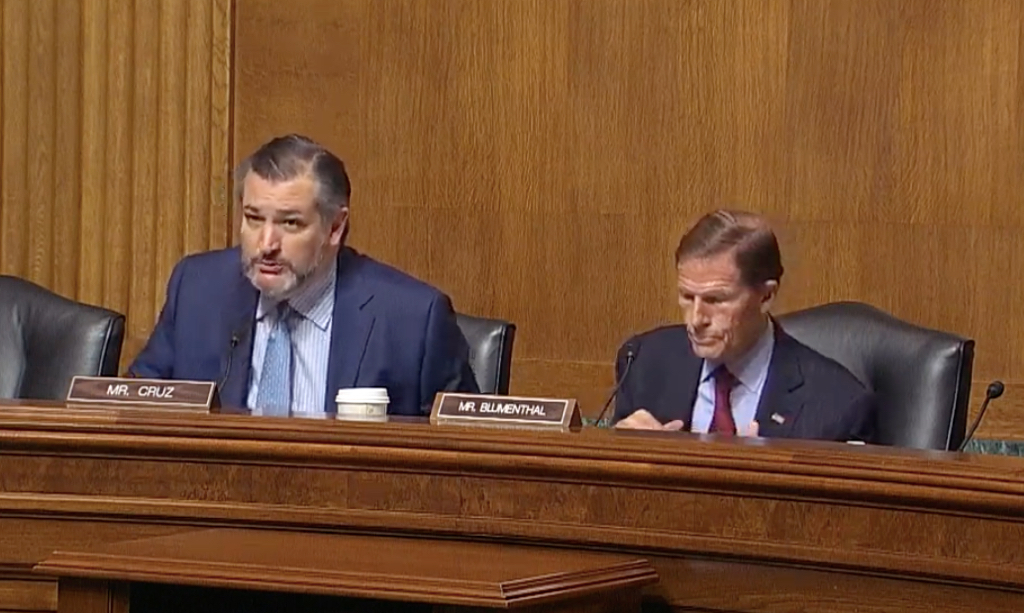

Sens. Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn., and Ted Cruz, R-Texas, called for greater federal oversight of court-appointed conservatorships at a Senate Judiciary subcommittee hearing on “toxic conservatorships” Tuesday afternoon.

The hearing – named in reference to Spears’ hit single “Toxic” – preceded the singer’s Wednesday court hearing in Los Angeles, which will outline her father’s remaining timeline as the conservator of her estate.

“While [Spears] continues to fight to make her own decisions and to live her own life, we can and we must fight to reform these legal straight jacket arrangements that are potentially abusive and certainly a disservice to many people that are under them,” Blumenthal said.

Widespread social media outcry about the singer’s restrictive conservatorship, which is currently trending under the hashtag #FreeBritney, revived conversations about conservatorship reform at the federal level.

A conservatorship, called a guardianship in some states, is a legal arrangement in which the court appoints someone to assume responsibility over an individual who lacks the ability to manage their own personal or financial affairs.

A California court placed Spears under a conservatorship in 2008, following her public mental health struggles. The conservatorship, which Spears is now fighting to terminate, granted her father, Jamie Spears, full control over his daughter’s personal affairs and her estimated $60 million fortune.

Cruz, who reiterated that he is “emphatically in the Free Britney camp,” shared his outrage over the singer’s June 23 testimony, in which she stated that her conservators prevented her from removing her intrauterine contraceptive device after she shared her desire to have a baby.

“This type of forced prevention of childbearing and forced sterilization, sadly, goes on all the time in oppressive nations and communist countries like China,” Cruz said. “That is not somebody else’s choice to make. That is grotesque.”

The National Center for State Courts estimates that 1.3 million American adults are living under conservatorship or guardianship, with their guardians controlling approximately $50 billion in assets.

Nicholas Clouse, a 28-year-old forklift operator, testified about his own experience with conservatorship in his home state of Indiana. After he suffered a traumatic brain injury in a 2011 car crash, Clouse agreed to the arrangement, with little understanding of the freedoms he was surrendering.

Though Clouse continued to earn money and raise a family, he required parental permission to make basic financial decisions, like buying diapers for his newborn child.

“I could make medical appointments for my daughter, but I was not allowed to make them for myself,” Clouse said, noting that the arrangement made him feel “worthless.”

Prianka Nair, co-director of the Disability and Civil Rights Clinic at Brooklyn Law School, said guardianships are imposed more frequently than they should be and are nearly impossible to terminate.

“You die a civil death when you’re placed under a guardianship,” Nair told Medill News Service. “There is a very, very limited set of circumstances where a guardianship is useful or has a benefit for someone, and that need needs to be reassessed frequently and controlled very tightly so that arrangement doesn’t become coercive.”

Though Cruz and Blumenthal shared their desires to improve data collection on existing conservatorships and guardianships, Syracuse University law professor Nina Kohn said limiting federal intervention to data collection would be a “terrible missed opportunity.”

Guardianship is a state-level issue, but Kohn said the federal government could improve the system across the board by providing funds to help states adopt legal reforms that would improve their monitoring of guardians.

“It’s not that we don’t know what to do, it’s that we don’t have the political will to do it,” said Kohn, who concentrates in elder law. “Simply having more data showing that we’re doing it wrong won’t change that.”