WASHINGTON– House lawmakers agreed Thursday that they want to limit the many US military actions underway across the world.

But there’s little consensus on how to reform the laws that have authorized all of those military operations.

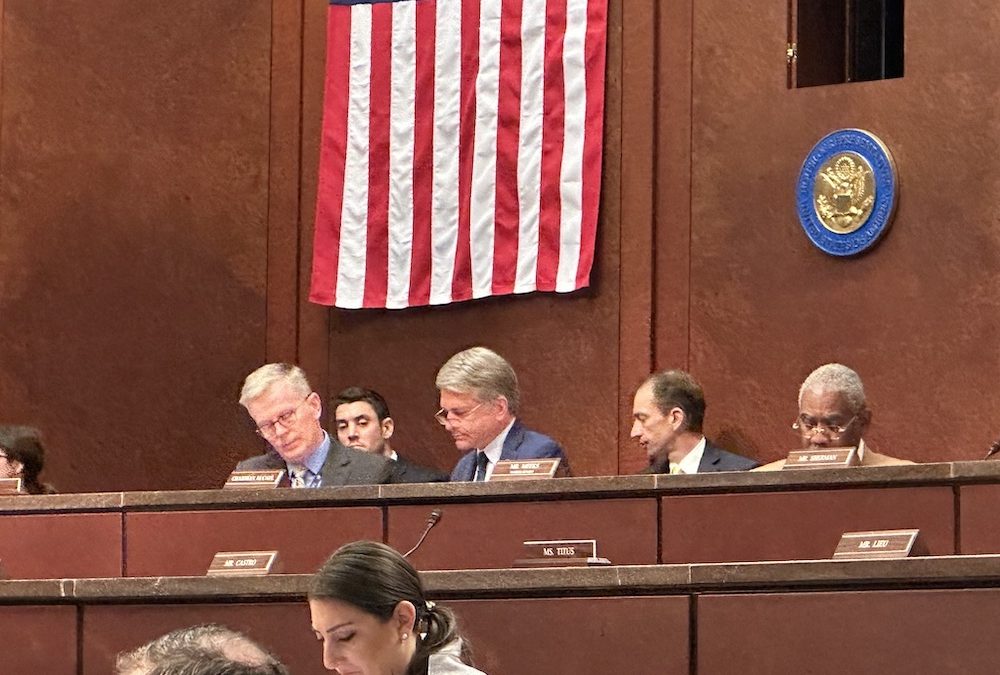

“War should not be on autopilot,” said House Committee on Foreign Affairs Chairman Rep. Michael McCaul, R-Texas, during a hearing on the authorizations. “Congress owes our troops a clear commitment to the missions we’re asking them to entertain.”

Lawmakers readily agreed that the military can’t operate overseas endlessly. But so far there’s no roadmap on what new authorizations might look like for the use of military force abroad. McCaul and other lawmakers expressed hesitation on a complete overhaul, citing continued threats from terror groups operating in Africa, and others backed by Iran.

The two laws in most need of reform are from 2001 and 2002. The 2002 law authorized U.S. forces to invade, and remain in, Iraq.

But it was the 2001 law, barely more than a page in length, that allowed the Global War on Terror to balloon into a truly global endeavor. The few paragraphs gave broad permissions to the president to use all necessary force against the people or groups behind the 9/11 attacks.

What began as a pursuit of Afghanistan-based Al Qaeda stretched to include other terrorist groups, including factions of ISIS across swaths of the Middle East, Africa, and Asia.

Rep. Gregory Meeks, D-N.Y., noted that in 2001, the senior Democrat on the committee, said Congress could not have imagined it being used as broadly as it has been.

Scott Anderson, a Senior Fellow at Columbia Law School’s National Security Law Program and a former attorney-advisor at the Department of State, was skeptical that Congress will take action.

“We’ve had this conversation before, and we’ve been having it for a long time,” he told Medill News Service over the phone. “It’s not clear to me that there’s a real route forward.”

“Most of the Congress agrees there should be more oversight,” he continued. “But the process of getting to the point you’d actually have agreement between the parties and presidents is a really heavy political lift.”

Anderson points to a bill that the Senate passed earlier this year to repeal the 2002 law. No action has been taken in the House.

Rep. Dina Titus, D-Nev., highlighted that inertia during Thursday’s hearing, pressing Undersecretary of State for Political Affairs Victoria Nuland on whether or not the Biden administration wishes to replace the 2002 Authorization for Use of Military Force, if Congress repeals it.

“We don’t see the need to replace the 2002 AUMF,” Nuland said.

“If they’re really serious about reforming this process, we’ve got the vehicle right there,” Rep. Titus said of the Senate-approved bill. “Why not use it and move forward?”