WASHINGTON– NCAA leadership and other leaders of collegiate athletics requested congressional involvement this week in governing how athletes profit off of their name image and likeness.

Two years ago, the Supreme Court shook up the relationship between athletes and their colleges when it issued the Alston decision, which ruled that the NCAA rules limiting education-related compensation violated antitrust laws. Shortly afterwards, the NCAA voted to allow athletes to profit off of their name image and likeness, which was previously against their bylaws.

In the two years since the Supreme Court issued the Alston decision, 32 states have created different laws governing student-athletes. These different laws, which place different requirements on student athletes, have made it hard for the NCAA to enforce its own bylaws and protect athletes from exploitative companies.

Some senators from both parties said the federal government needs to step in to create equal opportunity for all athletes. Several senators have drafted bills but none have been introduced.

“If this committee does not act within a year, this thing is going to be an absolute mess, and you will destroy college athletics as you know it,” said Senate Judiciary ranking member Lindsey Graham,R-S.C.

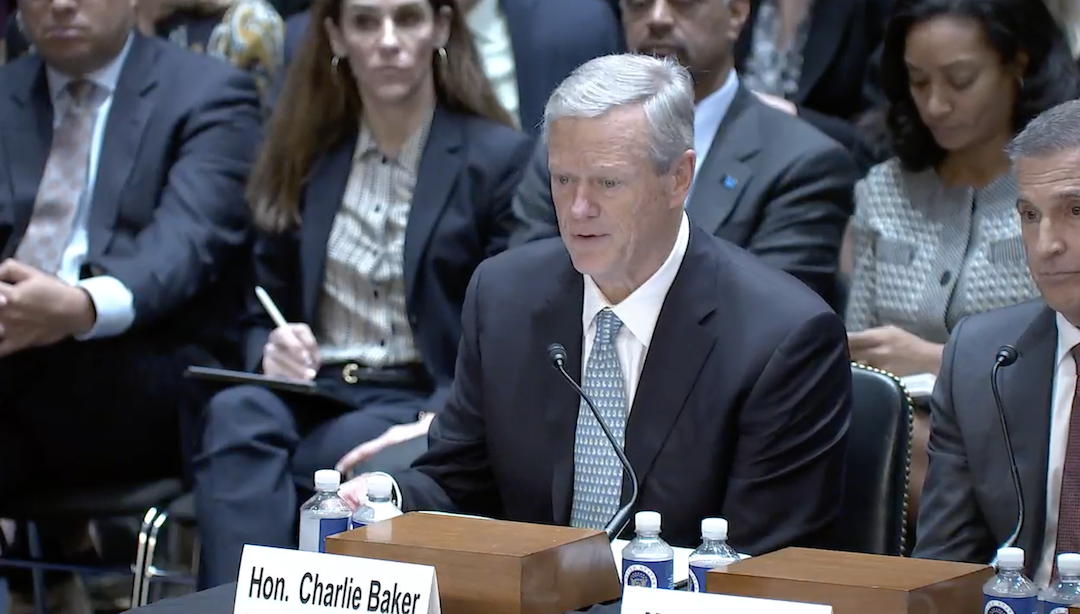

NCAA president Charlie Baker testified that student athletes said the current patchwork of laws is “incredibly confusing for them to navigate.” He stated in his written testimony that congressional intervention would be important for eliminating some of the confusion by ensuring student athletes can get fair contracts from reputable agents.

He and his peers also voiced their concerns over making athletes employees of the university that they attend.

“The elected student athlete representatives from all three divisions are on record saying the same thing, they fear the current legal landscape, turning them into employees and they have called for action,” Baker said.

Baker said he would not comment on a complaint filed by the NLRB that supported treating athletes as employees. However, he said that he fears it could lead to all student athletes to be granted employee status. If that happened, thousands of interscholastic programs likely would be eliminated, Baker testified.

For smaller universities that do not profit off of their athletic programs, employing student-athletes would jeopardize their education.

“They don’t want to have to apply for posted positions when what they’re really going for is an education. They don’t want to go through the state work comp system for their injuries. They don’t want to punch a time clock worried about what might be compensable time,” said Jill Bodensteiner, Vice President and Director of Athletics, Saint Joseph’s University.

A university like Saint Joseph’s would have to transition financial aid to wages in order to stay competitive, she said. This would make the student athlete subject to taxation. It would also eliminate opportunities for international athletes, who would not be able to compete.

Though multiple pieces of legislation are in discussion, they each take different approaches.

A source familiar with the draft bill by Sen. Richard Blumenthal, D-Con., Sen. Corey Booker, D-N.J., and Sen. Jerry Moran, R-Kan., said that their draft bill takes into account the size and scope of universities in order to protect non-revenue generating sports. It does not address the issue of employment. However, Sen. Blumenthal acknowledged during the hearing that he heard calls to include this in future legislation.

However, a draft bill by Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, would preempt state and local laws and explicitly state that athletes should not be employees.

“There’s a real risk that if Congress does not act and act quickly, that we risk doing enormous damage to a system that is providing enormous benefits to millions of Americans,” said Sen. Cruz.