WASHINGTON — Detroit police used facial recognition technology to investigate an instance of stolen watches four years ago. The system matched a photograph from the store to the man they eventually arrested.

Except he didn’t do it.

The police department falsely arrested Robert Williams after the software misidentified him. As a Black man, Williams was at a higher risk of being misidentified, according to academic research.

Williams took his case to the American Civil Liberties Union and he decided to sue the city for his wrongful arrest. The case is ongoing.

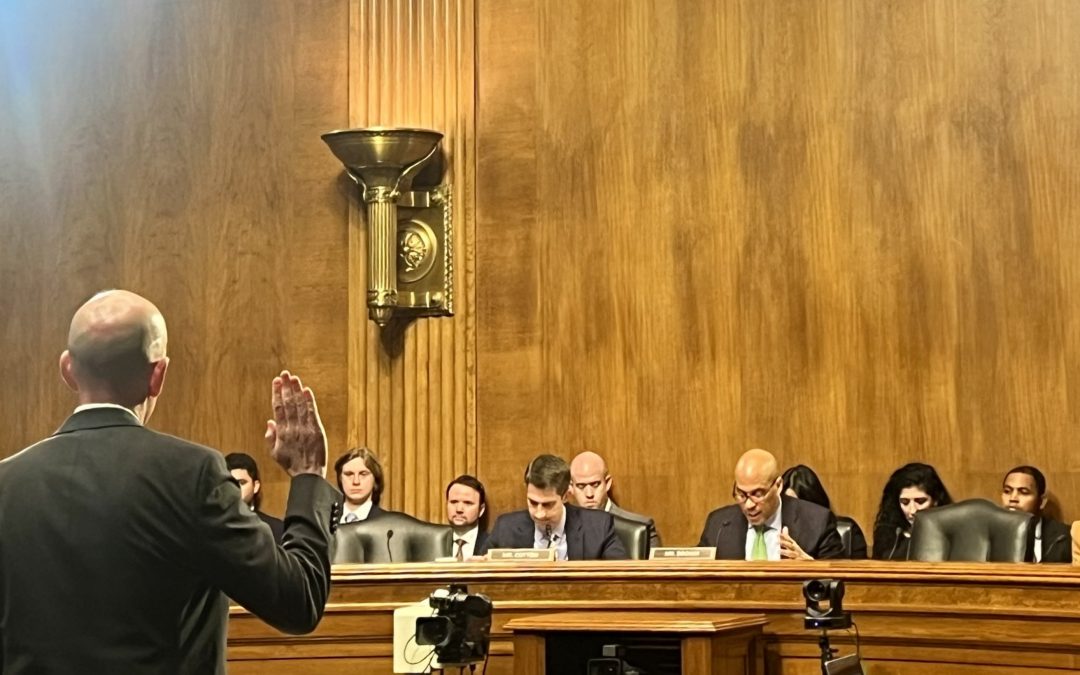

How to avoid discrimination while using facial recognition software was among many topics US senators raised during a hearing Wednesday about the innovations and risks of AI in criminal investigations and prosecutions.

During the Senate Subcommittee on Criminal Justice and Counterterrorism hearing, Sen. Alex Padilla, D-CA, cited a Government Accountability Office (GAO) report that found several federal law enforcement agencies failed to require civil rights training when using facial recognition software.

“This lack of training is troubling given that the technology has been shown to produce biased results, particularly when it involves identifying Black and brown persons,” he said.

Other senators seemed more willing to embrace AI in criminal investigations.

“AI is consequential in our society as a whole in ways that many of us can’t fully imagine– Both in the possibility and the promise, as well as the potential problems.” said the Subcommittee Chairman Sen. Cory Booker, D-NJ, in his opening remarks.

While the three expert witnesses differed on the use of AI in criminal investigations, they all agreed that the technology has the potential to increase law enforcement’s accuracy and efficacy.

Throughout the hearing, the witnesses each agreed that the agencies relying on AI technologies should be transparent about their use of them.

One witness, Assistant Chief of the Miami Police Department Armando Aguilar, discussed how he helped integrate facial recognition into his department. Aguilar also currently serves as a member of the National Artificial Intelligence Advisory Committee (NAIAC), which provides AI-related advice to the President and the National AI Initiative Office.

After he read a news article raising concerns about police use of facial recognition technology, he said his department consulted with local privacy advocates and tried to address their worries about Miami Police policy.

“We’re not the first law enforcement agency to use facial recognition or to develop [facial recognition] policy, but we were the first to be this transparent about it,” Aguilar said.

He said his department treats facial recognition matches like an anonymous tip, which still need to be corroborated with testimonies or other evidence.

“We laid out five allowable uses: criminal investigations, internal affairs investigations, identifying cognitively impaired persons, deceased persons, and lawfully detained persons,” he said.

Another witness at Wednesday’s hearing, co-director of the Berkeley Center for Law and Technology and an assistant law professor, Rebecca Wexler, raised more concerns for the future of AI than her fellow witnesses.

Sen. Booker told her, “you obviously had a lot of concerns in your testimony.” During questioning, she responded by clarifying that she is neutral about AI technology.

“The technologies themselves are not the issues— The legal rules that we set up around them to help us ensure that they are the best, most accurate and effective tools and not flawed or fraudulent in some way,” she said.

Wexler cautioned that AI is often used by law enforcement trying to prove guilt, which could make the systems biased.

“This may bias the development of technologies in favor of identifying evidence of guilt rather than identifying evidence of innocence,” she said. “So any support Congress could give to AI technology’s design to identify evidence of innocence would be very promising.”

Experts not present at the hearing also raise pros and cons of facial recognition technology.

Divyansh Kaushik, the associate director for Emerging Technologies and National Security at the Federation of American Scientists, referenced how the Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI) has used the technology to identify Jan. 6 insurrectionists, who were mostly white Americans.

“The question becomes not just of an impact of a system, but of how the system is put in place and used,” he said.

Facial recognition systems more frequently fail when the person being identified is not a white male, according to research conducted by the National Institute of Standards and Technology.

Deputy Director of the ACLU Speech, Privacy, and Technology Project Nathan Freed Wessler said police shouldn’t use this technology because of the high risk that the software is biased and misidentifies people of color. Wessler is one of Williams’ lawyers at the ACLU.

He said that he has seen policymakers who take this issue seriously, but that he has also seen hundreds of police departments across the country “where police have been more or less free to just experiment at their whim.”

Wessler said policymakers shouldn’t just consider the perspective of law enforcement, but also need to hear about the experience of everyday citizens, such as his client Robert Williams, whose case was not explicitly mentioned at Wednesday’s hearing.

“These aren’t just academic questions. These are questions that have extraordinarily serious effects on real people’s lives,” he said.