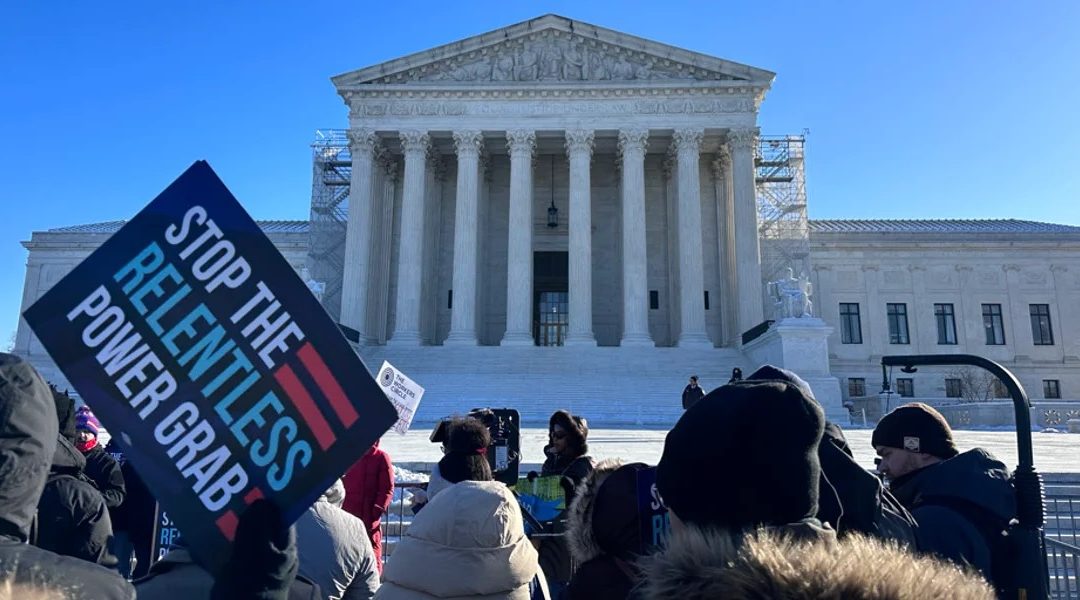

Activists gathered outside the Supreme Court on a frigid January morning to advocate for one the most consequential legal doctrines that you’ve probably never heard of.

Participants, representing groups supporting everything from environmental policy to the rights of the disabled, braved the wind and snow-lined sidewalks of Capitol Hill to urge the justices to uphold the 40-year-old practice of courts deferring to federal agencies when they create regulations that reasonably interpret federal law.

The so-called Chevron doctrine has been used scores of times to justify agencies’ decisions to fight pollution, protect workers’ rights and provide Americans with affordable access to health care. It has also been used to bolster conservative causes, most recently during Donald Trump’s presidency to roll back Obama-era environmental rules the Republican administration felt were overly restrictive.

Later that morning, the Supreme Court heard arguments in two cases that challenge the Chevron doctrine and the authority federal agencies have gained through it. The court, which is dominated by Republican-backed justices, can shift the balance of power from the president to the judicial branch.

The cases – Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo and Relentless Inc. v. Department of Commerce – both focus on Atlantic herring fisheries, which are regulated by the National Marine Fisheries Service. Under the Magnuson-Stevens Act, the agency required herring fishermen to pay for a mandatory at-sea monitoring program. Loper Bright and Relentless both sued, arguing that the fisheries service stretched the law beyond its original intention.

The demonstrators outside the Supreme Court said agencies’ interpretations of countless laws that protect people and nature are at risk in the case. Several protesters waved signs that read, “Stop the relentless power grab.” Across the way, a smaller group advocating for the court to strike down the doctrine stood silently. A few held signs saying, “It’s time to stand up for the little guy.”

Erin Jackson-Hill, executive director for Stand Up Alaska, a nonprofit dedicated to increasing civic engagement, addressed the crowd.

“It is imperative that we remain vigilant and steadfast in our defense of this doctrine, as it plays a pivotal role in maintaining the balance of power and preserving the integrity of our legal system,” she said.

One demonstrator commented that she had never heard of the legal doctrine before the case went to the Supreme Court but now understands how important it has been.

The Chevron doctrine comes from the 1984 case Chevron U.S.A. Inc. v. Natural Resource Defense Council, Inc. The Supreme Court ruled that courts would defer to federal agencies when statutes are ambiguous. Such rule-making, the court said, is only appropriate when the agency’s interpretation is reasonable and Congress had not spoken directly on the issue.

In practice, Chevron allowed the Environmental Protection Agency to use the Clean Air Act, which had not seen any major changes since 1990, to propose stronger passenger vehicle emissions standards, including as recently as last year.

Chevron also allowed the Department of Housing and Urban Development leeway to implement the Fair Housing Act, which protects people from discrimination when renting or buying a home, or seeking a mortgage. Under Chevron, the department was able to set rules for how landlords and banks avoid discrimination.

If the justices overrule Chevron, they would give the courts much more power to challenge and direct the way that agencies implement policy, according to Devon Ombres, a senior director for the Center for American Progress, a liberal think tank.

In total, according to some experts, federal appellate courts have cited Chevron more than 5,000 times. Ombres predicts that if it gets overturned, industries would overwhelm federal courts with challenges to regulations.

The Supreme Court’s three liberal members underscored the importance of Chevron, saying it allows agencies to govern when the law “runs out,” as Justice Elena Kagan put it.

Kagan explained that members of Congress create laws knowing that there will be gaps in their knowledge as well as future advances. She used the example of Congress attempting to make laws regulating AI.

“Congress knows that this court and the lower courts are not competent with respect to deciding all the questions about AI that are going to come up in the future. And what Congress wants, we presume, is for people that actually know about AI to decide those questions,” she said.

She also peppered the attorney for Relentless, Roman Martinez, with hypothetical questions that could face courts if Chevron were to be overturned.

“Is a new product designed to promote healthy cholesterol levels a dietary supplement or a drug?” Kagan asked the attorney.

Martinez said it would depend on the “original understanding of the text of that statue read in context” and he would not directly answer the question.

The six conservative justices seemed to agree that, under Chevron, courts have been too deferential to federal agencies. (The Supreme Court has noticeably ignored citing the doctrine in cases where it would be relevant during recent oral arguments.) They discussed the consequences of rejecting or narrowing Chevron.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh criticized Chevron by pointing out that judges have no control over agencies ability to “flip-flop” their interpretations of laws passed by Congress.

“Chevron itself ushers in shocks to the system every four or eight years when a new administration comes in,” he said.

Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Neil Gorsuch suggested that a better model would be the ruling in Skidmore v. Swift & Co., which allowed a federal court to determine the appropriate level of deference. But Kavanaugh was skeptical of the deference courts could give federal agencies under Skidmore.

It was unclear how the court would move forward, but it seems unlikely to both defenders and opponents of Chevron that the doctrine will continue to have the same sway over U.S. policy that it has had for 40 years. The likely outcome will shift power away from the executive branch and give more to Congress and the courts.

“The least likely thing to happen is for the court to just leave Chevron as it is,” said Adi Dynar, an attorney and separation of powers expert for Pacific Legal Group.