WASHINGTON – The arrival of the presidential primaries to South Carolina has kicked off the election season, but the Supreme Court has yet to announce its decision in a case that will determine the fate of the state’s 1st Congressional District.

The case of Alexander v. the South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP has drawn the interest of numerous voting rights groups, which have voiced fears about how a ruling in favor of South Carolina could allow for racially discriminatory redistricting to be more easily disguised as partisanship.

“I’m on pins and needles … I can tell you that voters are concerned about this case,” said Barbara Arnwine, president and founder of the Transformative Justice Coalition, a nonprofit group focused on critical justice issues and civil rights. “People asked me ‘what did I think would happen?’ and their fear is that they will not be able to have fair representation that they deserve in Congress.”

Oral arguments were heard in the Supreme Court back in October, after a South Carolina District Court in January 2023 found that the 1st Congressional District had been racially gerrymandered, following the 2020 census redistricting. The state legislature appealed, claiming the shifts were the results of partisan gerrymandering, or redistricting done to serve the interests of one political party over the other.

Parties involved with the case had asked the Supreme Court to decide by January, so that any necessary changes to the district could be in place prior to the 2024 election. That deadline has come and gone.

The 1st District had in recent years been won – and then lost again – by a Democrat in races with narrow margins. So, the state’s Republican-led legislature sought to create a stronger foothold for their party following the 2020 census.

When the new maps were adopted in 2021, 140,000 residents had been removed from District 1, including nearly two-thirds of the Black population in Charleston County.

Out of the 12 precincts with the highest Black voting age populations, 11 were moved into District 6, which is held by Jim Clyburn, the only Democrat and only Black representative from South Carolina in the US House. An additional 53,000 residents from Clyburn’s neighboring congressional district were shifted into the 1st District.

The new boundaries seemed counter to the “least change approach” that was applied throughout the rest of the state, which aimed to maintain the boundaries of the 2011 map as much as possible.

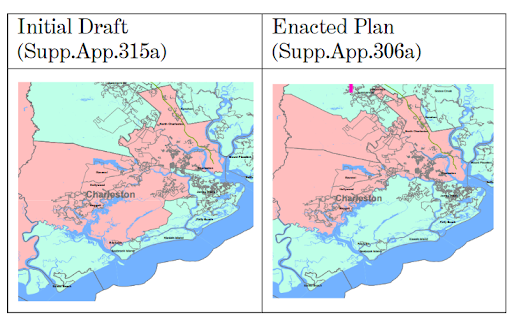

An initial redistricting draft would have kept a larger percentage of black voters within the boundaries of the 1st District than the map later adopted by the state legislature. (From p. 22 of the appellee’s motion to affirm)

“This massive movement disregarded the least change approach that the state applied state-wide and that mapmakers admitted they abandoned only in Charleston County,” said Leah Aden, lawyer representing the NAACP.

Along with a voter from the 1st District, the South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP sued the state legislature, citing violations of both the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause, which prohibits racial gerrymandering and voter dilution, and the 15th Amendment.

Thomas Alexander, the president of the state Senate, and other Republican leaders of South Carolina’s legislature argued that the new district lines had been drawn based on political data to create a partisan gerrymander – a practice that fell under the state’s purview following the 2019 Supreme Court decision to place gerrymandering outside the scope of federal courts.

State mapmakers acknowledged that racial data had been reviewed for the making of the map. Still, they stated that they had primarily relied on election data for redistricting in the 1st District – specifically, the 2020 presidential election, where 90% of black voters in South Carolina had voted for President Joe Biden.

“The Republican legislature in South Carolina acknowledges that it was trying to make this particular congressional district a safer seat for Republicans,” said Richard Pildes, a New York University Professor specializing in legal issues concerning democracy. “These cases turn on whether the legislature in the redistricting process moved people around based on their voting patterns, which is constitutional, or whether it moved them based on their race.”

In January 2023, a panel of three federal district judges unanimously ruled that South Carolina’s 1st District was the result of racial gerrymandering, and ordered future elections be paused and the map redrawn.

The case was appealed though, and landed before the Supreme Court on Oct. 11 2023, where justices clashed over whether there was substantial evidence to support the lower court’s findings, and how much – or how little – they should rely on those findings when determining if the lower court had made errors in its ruling.

John Gore, representing the South Carolina legislature, argued that the lower court’s decision hinged on “very weak circumstantial evidence,” based on the opinions and analysis from the opposition’s experts. Justice Samuel Alito, Chief Justice John Roberts and additional members of the court’s conservative majority questioned whether there was substantial enough evidence to prove race, not politics, was the predominant factor driving the changes, in a state where Black residents overwhelmingly voted Democrat.

“Disentangling race and politics in a situation like this is very, very difficult,” Roberts said.

However, Justice Elena Kagan argued that the NAACP effectively persuaded the district court that “race, not politics, was the predominant consideration,” and that in consideration of the lower court’s findings, claims about the legislature’s intent were “irrelevant.”

Kagan also expressed skepticism over the state legislature’s argument that the district court had wrongly discarded testimony from the senate-appointed map maker that race was not used in determining the new 1st District map.

“The information the map drawers had on their computer was a single presidential election year voting data and then lots of race data,” said Kagan. “And everybody can tell you that if you really want to draw a stable partisan gerrymander, you do not rely on a single presidential year election data.”

The court’s other liberal justices, including Justice Ketnaji Brown Jackson, stressed that the justices were primarily meant to examine the lower court’s findings for errors, rather than debate the facts of the case again.

Legal experts and advocates have struggled to predict the outcome of Alexander. In June, 2023, in Merrill v. Milligan, the court ruled in a 5-4 decision that the State of Alabama had engaged in voter dilution based on race. This surprised voting rights advocates who worried the court would curtail voting rights as it had in other recent cases, such as Rucho v. Common Cause, the 2019 partisan gerrymandering case.

With that in mind, legal scholars like Pildes outlined three potential outcomes for the South Carolina case. The Supreme Court could choose to affirm the findings of the lower court and rule that the State’s district was unconstitutionally gerrymandered and the district needs remapping. Alternatively, it could overrule the lower court’s decision, and keep the current 2021 map in place.

“We’re afraid that [overruling] would signal a significant withdrawal of the federal courts in this area of voter protection and election fairness,” said Arnwine, founder and lawyer for the Transformative Justice Coalition.

There’s also a third possibility. The court could review the case and find that the lower court had evaluated the case under the wrong standards – as suggested by Assistant U.S. Solicitor General Caroline Flynn, who represented the Federal government during the October oral arguments.

In that case, Alexander could be sent back down to the lower courts with clarified legal standards, to be reevaluated.

But with the 2024 election already on the horizon, and a limited amount of time to legally make changes to election procedures, South Carolina’s 1st District could be left in uncertainty, warned Arnwine, if there isn’t a decision – and map – in place soon.

“I don’t mind them taking time to reach the right result,” she said. “I just really hope that the court can make a good decision soon. And I hope they reached the right decision, and that they come up with some new statutes and new standards that make it much harder to defeat the pretext of partisanship when it’s really a racial gerrymandering.”