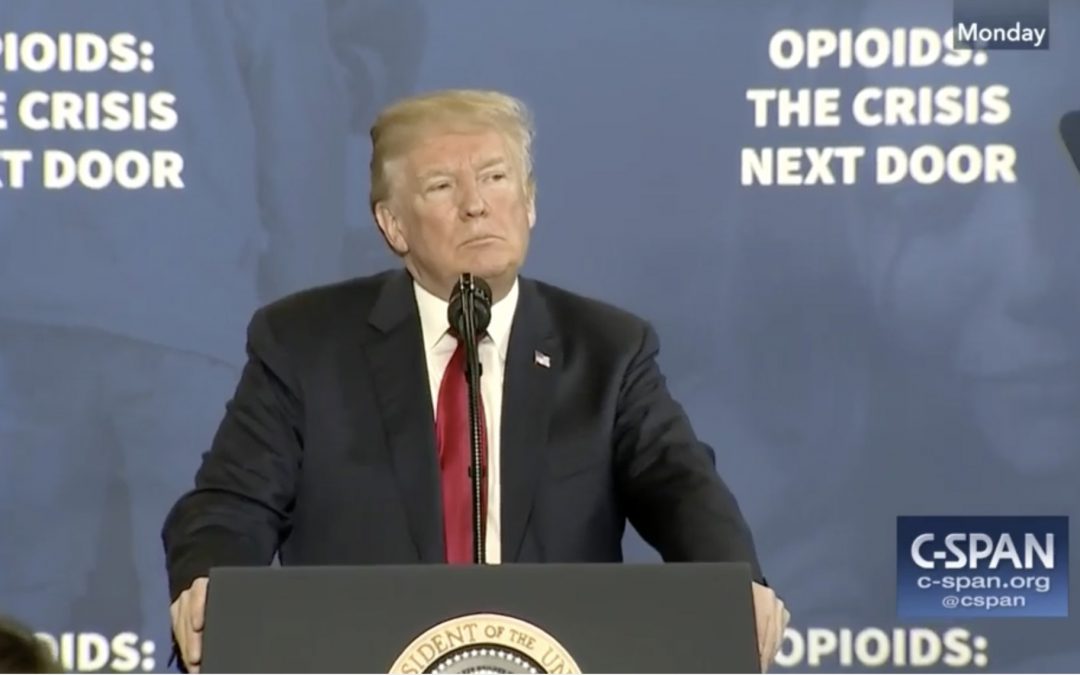

WASHINGTON — President Donald Trump appeared in New Hampshire on Monday to reaffirm the importance of solving the opioid crisis and announce new strategies for dealing with the problem.

The president’s speech primarily focused on stricter law enforcement measures like strengthening the patrolling of the southern border with Mexico and even using the death penalty as a tool to deter and punish drug dealers.

Many experts have questioned the effectiveness of Trump’s get-tough stance on drugs and warned that it might do little to stem the rise in the death rate from drug overdoses.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, more than 64, 000 people overdosed from drugs in 2016 — a rise of over 10,000 from the previous year. About 42,000 overdoses were from opium based drugs.

The Medill News Service spoke with Dr. George Benjamin, executive director for the America Public Health Association, concerning whether a law-enforcement centered approach is the more effective way to combat the opioid crisis.

Below is a condensed version of the interview.

Q. Is taking a more law-enforcement-centric approach in combating the opioid crisis an effective solution to the problem?

Benjamin: You need to use . . . a treatment, recovery, and prevention strategy at the center of this.

Certainly, the law enforcement component can be wrapped around to provide some ancillary support for it, because you do have to cut off the supply of drugs in many ways. But the problem with the opioid epidemic is it has many, many facets.

If you don’t do it from the patient’s perspective, you don’t get to address the Hepatitis C; the Hepatitis A; the issues around depression, hopelessness, domestic abuse, child abandonment.

All those things that we know go with a substance abuse problem, don’t get addressed [under Trump’s approach] because it becomes focused as a criminal justice issue and not focused as a treatment, recovery issue.

Q. What are some of the specific problems that occur if the opioid crisis is seen as predominantly a criminal justice issue and other concerns are not being focused on?

Benjamin: So, people who become addicted because their doctors prescribed them medications, for a legitimate reason, who then—for a variety of reasons we don’t quite all understand—migrated to illegal drugs. What happens is, they become “bad people” and we treat them as “bad people” in the system.

We criminalize a disease process that was a medical process to begin with. We never resolve their underlying reason for the pain. And, they become the center of the issue, but from a legal perspective versus a treatment, care perspective.

The other thing that happens is they go underground. They don’t show up for care. They become very protective of interfacing with anyone because they don’t want to be criminalized.

Q. Could you explain a little about the complications that are created if all of the rhetoric surrounding the Trump administrations plan is focused on law enforcement? Does that skew how the public will view the opioid crisis?

Benjamin: If people think that you’re coming after them, then, again, they are not going to come out for care. They are going to be very suspicious by giving you the information that they have.

In fact, it may prevent you from getting to the drug dealers because they are not going to share that information of how they’ve transformed from a treatment aspect to getting illegal drugs. They’ll also do some things that are very destructive.

For example, they might not show up for needle exchange programs.

If they do migrate from opioids to [intravenous] drugs, then the might start exchanging needles versus going to clean needle programs. They won’t tell you when they are sick and you find out about they’re infectious diseases like Hepatitis A, which can be contagious, because they’ll hide from you. So, that poses a risk to the entire population.

Q. How do you take something that is so personal and individual, like drug addiction and drug rehabilitation, and extend that out to something that has now become a national issue?

Benjamin: We did it with HIV /AIDS and that is a very, very complicated disease process. We’ve done it with a variety of sexually transmitted diseases, other than AIDS, which again…you don’t want to know that you have an STD…it is very, very personal.

Substance abuse is not equivalent in many ways. I don’t want to confound the two disease processes. But I do want to say that they share the idea of it being very personal.

Particularly for someone who is using medication because they hurt, their doctor prescribed it for them. They’re addicted to that medication, but they don’t necessarily recognize their addiction.

It’s not just only personal, but there has to be an awareness part of this that they have a problem that needs to be dealt with.

Q. Do you think the crisis began with a lack of education in the population? Or, was it centered around over-prescription?

Benjamin: It is a complicated issue. It certainly started this time through probably over prescribing. And, the people that sell drugs, not paying attention to how many drugs go into a community and then picked up by the illegal drug community to push it to make a profit.

You also have a lot of kids who don’t know that these drugs are dangerous. And the fact that many of the pharmaceutical companies were telling their doctors that these were not addictive, the patients then heard that they were not addictive, and it turns out that they are terribly addictive.

So, there is an education component to this. But there is also a whole range of complicated other systems issues that we have to fix.

Q. Anything that you would like to add?

Benjamin: The one thing missing from the Trump plan—obviously missing—is the public health prevention part of this. They treat the prevention part as a very medicalized component. And, we know there are a whole lot of things we can do very well upstream from a public health perspective that need to be added overtly in the plan if we are going to be successful.

Q. Do you have any specific examples?

Benjamin: Doing studies that try and figure out why people make that transition from prescription drugs to illegal drugs; why they feel the need for that; how best to communicate this message to the public.

We know the “just say no” campaign did not work. It doesn’t work, by the way, for tobacco either. And, we did a lot of research to figure out what messages best work for the public. And, really how to deal with people’s engagement with our public health and health system to address drugs.

Q. Do you feel hopeful that the opioid crisis is something that can be combated effectively?

Benjamin: It’s complicated. It’s tough. But, with a good plan and meaningful number of resources applied in the right places, we can fix this problem.