[SWF]/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/brain.swf, 550, 400 [/SWF]

WASHINGTON – As NFL players reported to training camp last week, scientists at the National Institutes of Health said they will analyze the brain tissue of Junior Seau to help better understand the damage an NFL career can have on a player’s brain.

A group of retired National Football League players is suing the league for negligence in concussion prevention and treatment. The NFL’s recent collective bargaining agreement provided that the league and players would give $100 million for medical research, mainly for brain research.

Advances in research looking into traumatic brain injuries and the disease chronic traumatic encephalopathy have been possible, in large part, by the donations of the brains of late NFL football players who exhibited clinical symptoms of CTE before their deaths.

When Seau, a former New England Patriots and San Diego Chargers linebacker, committed suicide in May at age 43, police records showed he shot himself in the chest. Some believe Seau wanted to ensure his brain was salvaged so it could be used to study whether the effects of repetitive concussions could contribute to CTE.

In July, Seau’s family agreed to donate a portion of his brain to the National Institutes of Health for research.

“The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is not directly involved in an analysis of former NFL player Junior Seau’s cause of death, but physicians at NIH’ National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke conduct research on traumatic brain injury and have agreed to carry out an analysis of the autopsied tissue,” the NIH said Wednesday. “In order to protect Mr. Seau’s children’s right to privacy, NIH will not discuss the status of the tissue or any subsequent findings.”

Christine Baugh, research coordinator at Boston University’s Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy, said concussions have acute symptoms but it is what happens after the concussion that can lead to CTE.

“The brain is floating in the skull and when a football player is moving in one direction, then stops, the only way the brain stops is by hitting the skull,” Baugh said. “The brain is the consistency of Jell-O. When a concussion occurs the chemicals of the cells go awry. They are in an imbalance. Somewhere in the process of the cells recovering a protein is formed that causes long-term damage. Those proteins are characteristic to CTE.”

The BU center recently released a study on CTE that aims to show the connection between contact sports, repetitive brain trauma and CTE, which it notes can only be diagnosed postmortem.

Due to the fact that symptoms of CTE typically don’t show up until years after the concussive activity, “CTE is pathologically distinct from other neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease,” the study said.

“There is a common thread I find in the majority of the players – anxiety, depression and impulsivity, along with memory loss,” said Craig Mitnick, the lawyer representing some of the players in the class-action suit against the NFL.

When NIH researchers examine Seau’s brain, they may use a procedure that Boston University has used to study the brains of late NFL players.

The neuropathological analysis done on a cross-section of the brain uses dyes to show the accumulation of the hyperphosphorylated tau protein. This protein accumulates after a concussive or subconcussive event and is characteristic of CTE.

Visually, the brain with accumulations of the hyerphophorylated tau protein shows various areas of brown on the brain. A brain not exhibiting this protein shows no brown areas.

According to the review, the areas of the brain most severely damaged by CTE “include the cerebral cortex and the medial structures of the limbic system (amygdala, mammillary bodies, hippocampus, etc.).”

The cerebral cortex includes the frontal lobe, which regulates decision-making, problem-solving, control of purposeful behavior, consciousness and emotions, according to the NIH website.

The BU review noted that the position a player plays is a factor in developing CTE.

“The Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy has found neuropathologically confirmed CTE in football players with no history of diagnosed or reported concussions (but who played positions such as lineman, with the greatest exposure to repetitive hits to the head).”

Baugh explained: “There are two main factors: how many hits and how forceful those hits to the head are. We see this in linemen. They may not receive hard hits but repetitive hits.”

Wide receivers and quarterbacks, on the other hand, are hit less but with more force, she said. “What we don’t know is whether these things make a difference. If you add up a bunch of little hits is that the same as one big hit? We are working on that in our research to figure it out down the road.”

Baugh emphasized that traumatic brain injury is the necessary variable in chronic traumatic encephalopathy.

“What is really sad is that in all too many of the football players’ brains we’ve looked at, we’ve seen CTE in their brains,” she said.

The limbic system, as mentioned above, is also damaged by CTE. According to the National Institutes of Health, it governs emotions and behavior. It also is involved in formation of long-term memory and the sense of smell.

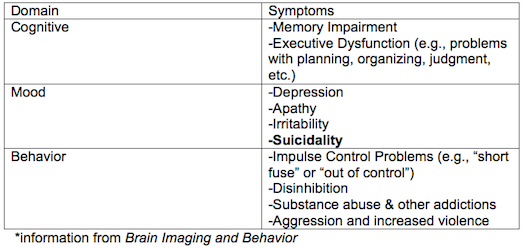

Damage to these areas, limbic system and cerebral cortex, is consistent with the cognitive, mood and behavioral symptoms that are characteristic of chronic traumatic encephalopathy in retired football players, the BU study said.

Baugh and her colleagues now are trying to find ways to diagnose CTE while a person is alive; currently, the neurodegenerative disease can only be diagnosed post-mortem.

“We know the clinical signs and symptoms (mood, behavior, cognitive) but now we are trying to use bio markers to indicate the biological changes that happen to the brain cells after being a hit to the head,” Baugh said. “Since the disease is caused by chemical changes we are looking to see if we can find the changes in the cerebralspinal fluid because the brain rest in the cerebralspinal fluid.”

Baugh also noted how much support the Center of the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy has received from the football community.

“I’ve been extremely moved by the NFL community and their support,” she said. “Some people, they were teammates of the players we’ve examined and they’re really concerned.”

Mittnick agreed that the NFL financial support of research is good for the future of the game, “but it doesn’t address the past.”

“(NFL Commissioner)Roger Goodell needs to sit down with the former players and their families and see what they are going through, see what I see,” Mittnick said.

Follow Malena @mcaruso2 on Twitter