When she first received the samples at her lab, Anuradha Chowdhary figured it was a local problem.

It was 2009, and the fungus, which had been isolated in two intensive care units in Delhi, India, couldn’t be identified by routine methods. So samples were sent to the University of Delhi lab where Chowdhary, a professor and clinical microbiologist, set to work.

Her lab identified it as Candida auris, a close relative of other Candida fungi that cause oral thrush in infants and vaginal yeast infections in women. But unlike other species of Candida, this one was resisting commonly used antifungal medications, and it could cause dangerous infections in hospital patients.

Right around the time Chowdhary’s lab identified it, C. auris started showing up in other countries. Since those first cases in 2009, it has emerged on five continents.

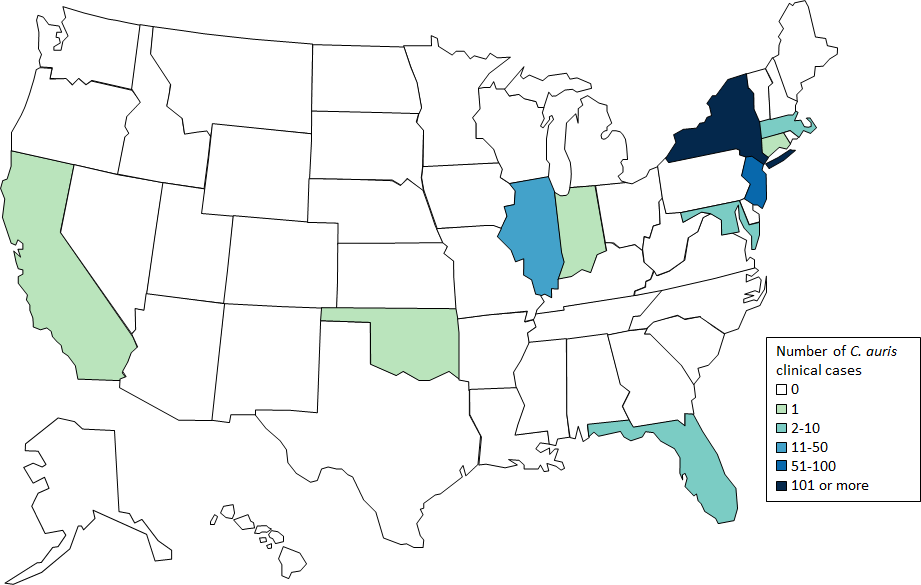

In the United States, where the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2016 first alerted health care facilities to be on the lookout, there have been 215 confirmed cases in 10 states as of January 31. That’s up from the seven first reported in the summer of 2016, according to data from CDC, which has been tracking the fungus’ movement through the country.

“You won’t get it riding on the subway,” said Snigdha Vallabhaneni, a CDC epidemiologist. Candida, a yeast, often lives harmlessly in our bodies, from our mouths to our gastrointestinal tracts. It’s when it gets into the bloodstream that it causes problems, Vallabhaneni said.

Unlike common thrush or yeast infections, these invasive bloodstream infections often result in prolonged and costly medical stays, and an increased risk of patient death.

About 40 percent of U.S. patients with C. auris have died, according to CDC’s records. But since those patients had other serious medical conditions, it’s unclear whether C. auris was a factor in their deaths.

Regardless, Candida auris poses a risk for patients, mostly in hospitals and long-term care facilities. These patients have often been in clinical care for a long time and rely on medical equipment like breathing tubes and catheters, which offer an opportunity for the fungus to grow and eventually enter the body.

Additionally, said Vallabhaneni, the apparent ease with which it travels from patient to patient makes clinical environments prime spots for outbreaks. And since it’s new, many labs fail to recognize it in the first place. They need specialized technology to do so.

That’s why CDC has been targeting its prevention and education efforts toward health care staff – who are in charge of maintaining infection-free environments – and the labs tasked with identifying C. auris. Much of the agency’s work has focused on building laboratory capacity throughout the country so those labs can identify the fungus, Vallabhaneni said.

As far as Candida go, Candida auris is unique.

It’s not exactly clear why the fungus is just appearing now. Scientists can trace what may be its earliest appearance back to a 1996 case in South Korea. But when they compare genomes of samples taken from different regions of the world, they find the genes are similar within regions, but different among regions. It’s as if C. auris has sprouted up independently in different parts of the world.

But wherever it is, it always seems to show the same stubborn resistance to traditional antifungal medications. C. auris “acts much more like a bacterial superbug” than other Candida species, Vallabhaneni said.

One likely reason it’s become resistant to so many antifungals is because doctors commonly prescribe those medications without being certain of the diagnosis, Chowdhary said. She and a team of scientists recently published research showing that a certain mutation in the fungus’ genome may account for its widespread resistance to fluconazole, one of the most common medications used to treat Candida infections.

In some cases throughout the world, C. auris has developed resistance to all available medications. That hasn’t happened in the U.S. yet, but that’s why public health agencies like CDC are tracking its movements so closely.

Since C. auris was first identified, cases have been confirmed on five continents. (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

It’s a similar phenomenon to what commonly happens with antibiotics: The fungus (or, in the case of antibiotics, the bacterium) evolves to escape the medication, causing major concern for public health experts.

At the moment, one of the most promising treatment options for C. auris is echinocandins, a relatively new class of antifungal medication that the fungus has shown minimal resistance to. CDC recommends them for U.S. patients, though, as Chowdhary noted, echinocandins remain inaccessible to many patients in India due to their high cost.

For her part, Chowdhary is going to continue her research. The existing knowledge at this point is “meager,” she said, adding that further studies have to be conducted to understand why C. auris is emerging in so many countries and, equally important, how to keep it from evading treatment.

When she first encountered it in Delhi, “I thought it was just our problem,” she said. “I never imagined it would become so big.”