WASHINGTON – A year after the Trump Administration imposed tough limits on refugee acceptance, analysts say they are just beginning to see the effects of the decline on small businesses.

The executive order signed on Jan.27, 2017 lowered the refugee admission ceiling to 50,000 for fiscal year 2017, from the 110,000 admissions set by the previous Obama Administration. Historically, the number of admissions has ranged from 67,000 to 200,000 immigrants.

According to a report of the Refugee Council USA, a coalition of non-governmental organizations that advocates for refugees, the number has been lowered again, to 45,000 for the 2018 fiscal year. Yet a mere 6,704 refugees have arrived as of January, far fewer than was expected during the first four months of the new fiscal year.

If the flow of legal immigration into the country continues to plummet, it will exacerbate the shortages in the domestic labor market and go against the country’s historic humanitarian commitments, according to Jake Kuhns, the director of federal government relations for Cargill, Inc, a major grain trading and agricultural products company.

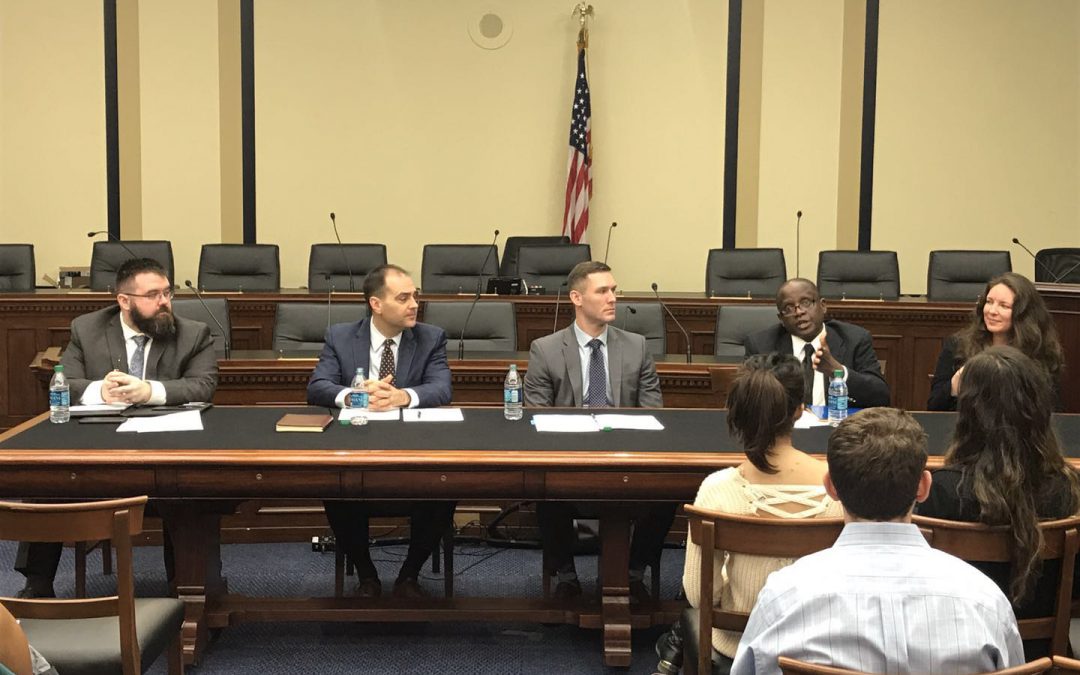

During an informational briefing on the current legislation impacting refugee communities hosted by the congressional refugee caucus, Kuhns said that many industries are experiencing severe labor shortages worsened by the Trump Administration’s crackdown on immigration – both legal and illegal.

Kuhns said that refugees are usually very hardworking and eager for a job. They have become the workforce essential in supporting housing development, restaurants and public schools. Without an adequate immigrant workforce to draw on, some businesses will have to close or raise their prices – resulting in higher costs for consumers and shortages of some services.

According to the Refugee Council USA, the average refugee participation rate in the workforce is 81.8 percent, exceeding the national average of 62 percent by almost 20 points.

Through collective studies of other state-by-state reports, the organization found, for instance, that the rate of refugees in Columbus, Ohio, who began their own businesses is double that of the general population.

In Lancaster, Pennsylvania, immigrants and refugees have helped the local manufacturing industry generate 1,062 jobs that would not otherwise have been created in the city. In Cleveland, refugee-owned businesses accounted for $12 million in area spending and offered 175 new jobs.

Scott Cooper, the national security director of Human Rights First, an international human rights non-profit, says it’s a misconception that Americans usually worry about too many refugees flowing in and taking their jobs.

“I think it’s wrongheaded to demonize refugees, and not to seek to be a leader in this global crisis,” Cooper said.