Each week, The Spokesman-Review examines one question from the Naturalization Test immigrants must pass to become United States citizens.

Today’s question: How are changes made to the U.S. Constitution?

In the aftermath of the Revolutionary War, representatives of the 13 colonies convened in Philadelphia in 1787 to discuss the power structure of their new country.

After living under British rule, the U.S. had “a very strong and healthy distrust of power, authoritative power,” said Jeff Feldman, a professor at the University of Washington School of Law. The states understood the necessity of a central government, but didn’t want to cede too much autonomy to create it.

The new Constitution, which replaced the Articles of Confederation that had governed the colonies during the war, limited the federal government compared with the states and set out the three branches: legislative, executive and judicial.

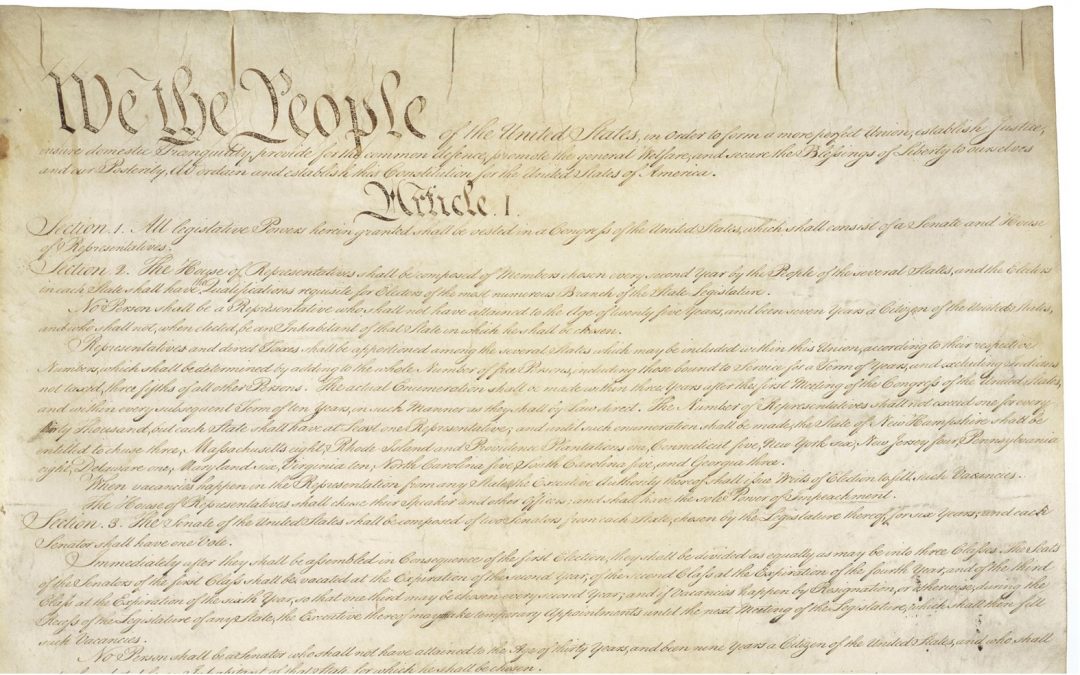

The preamble “We the People” was “a proclamation that the government exists at the behest of the people,” Feldman said. “The government works for us, we don’t work for it.”

Of course, that “we the people” preamble was limited in scope, written by and for white men – and the document itself included a “three-fifths” clause that devalued enslaved Black people in the tally for congressional representation. But for the people it represented – and now for the people it has since come to represent – it promised a balance of power between the people and the government.

“We don’t think of the federal government as having limited power because we all live in a world where the federal government exercises a great deal of authority over our lives,” Feldman said, but the federal government is largely limited to issues of commerce, national security and trade.

But the ratification of the Constitution was the product of extensive debates and negotiations, and there were “unresolved issues” around individual rights, Feldman explained.

“Article 5 of the Constitution provides that it can be changed,” said Garrett Epps, a professor at the University of Oregon School of Law who used to report on the Supreme Court for the Atlantic – and any changes are adopted fully into the original document.

So the delegates agreed that they would ratify the Constitution in 1789 to expedite the establishment of the U.S. government, but that they’d then turn to the issue of individual rights by amending the Constitution.

Two years later, they ratified 10 constitutional amendments – called the Bill of Rights.

‘Really, really difficult’

The 10 amendments, enacted together in 1791, were constructed “to embed in the Constitution the individual rights that we have come to take as part of our world,” Feldman said.

The Bill of Rights guarantees certain individual liberties and defines the relationship between an individual and the U.S. government. It sets out freedoms of speech, press and religion, among others – and protects individuals from government overreach like unreasonable search and seizure or self-incrimination.

Since the Bill of Rights, the U.S. has ratified 17 additional amendments to the Constitution – though more than 11,000 amendments have been proposed.

An amendment first comes to Congress as a bill that must be approved in both the House and the Senate by a two-thirds supermajority.

“You don’t need to do anything other than look at yesterday’s headlines to know how hard it is to get Congress to agree on anything,” Feldman said, “let alone agree by a two-thirds vote.”

If the bill makes it through both chambers of Congress, it goes to the states for ratification and must be approved by three-fourths of them – which means 13 states can block ratification.

An amendment can also be brought to the states if two-thirds of the state legislatures call a constitutional convention – but no such call has been successful to date.

“By design, amending the Constitution is really, really difficult. It’s hard, it takes a lot of agreement and it takes a long time,” Feldman said.

The proposed Equal Rights Amendment, introduced in Congress in 1923, was designed to codify equal rights for women after the 19th Amendment gave women the right to vote. The ERA was introduced in each subsequent congressional session until it passed both chambers in 1972.

The ERA was then given a seven-year deadline to meet the three-fourths state ratification threshold – and it failed.

“It had tremendous momentum” and “overwhelming support from the public and a majority of states,” said Epps, “but three-fourths is a pretty high supermajority.”

In 2020, Virginia became the 38th state to ratify the ERA, bringing the bill right to that threshold – but the measure is still stalled because it didn’t get to 38 by the seven-year deadline.

Despite the long odds of passing a constitutional amendment, there’s a benefit if lawmakers can achieve what seems nearly impossible because Congress can’t create legislation that contradicts the Constitution, said Dr. Upendra Acharya, who teaches constitutional law at Gonzaga University School of Law.

“The will of the people” is protected by the Constitution’s rigidity, Acharya said.

The high bar for passing an amendment is “the overall armor” to protect against the partisanship that sways Congress. And even attempting to push a proposal over that bar indicates how important that issue is to the lawmakers and constituents who back it.

“A lot of things that are amendments could have been accomplished by statutes enacted by Congress,” Feldman said, but addressing a big issue like free speech or voting rights with a constitutional amendment means “embedding it in a place where it’s going to be harder to change” and where it can “become more of the lasting fabric of our system of governance.”

‘It took a civil war’

Amendments are often a response to national issues or events – with a permanence and clarity unique from laws and Supreme Court rulings.

The 25th Amendment, which sets out the line of succession to the presidency, was enacted in the aftermath of the assassination of President John Kennedy. “It took a traumatic act to our country,” said Feldman, to prompt Congress and the states .

In 1971, the 26th Amendment lowered the voting age from 21 to 18. “During that period of time, we were shipping off a lot of young people to the Vietnam War who were getting injured and killed,” Feldman said, “and there was a strong sentiment that if people were old enough to fight and die for their country, maybe they were old enough to vote.”

The 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments formalized the legal and civil rights of formerly enslaved people after the end of the Civil War and the Emancipation Proclamation. But even with issues as fundamental to American law and liberties as these, “it took a civil war to provide an impetus” for their enactment, Feldman said.

Sponsors of the 14th Amendment “were concerned that, after the Civil War, the same people who ran the Confederacy were going to come back into Congress and take power and repeal all the civil rights laws that had been passed,” Epps explained. Changing the Constitution was a protection that made those new laws harder for Congress to challenge or repeal.

Other things just “clearly have to be done by amendment,” Epps said. The 17th Amendment changed a provision of the Constitution that originally said senators would be chosen by state legislatures and instead established a popular vote. The public mobilized and “basically forced the U.S. Senate as it then was to vote itself out of existence.”

Some still advocate for the ERA, while others say women’s rights are established enough by the existing equal protection clause and rulings of the Supreme Court, which has the power to clarify or narrow the parameters of the Constitution.

“But the most common English word that doesn’t appear in the Constitution is ‘she,’ ” Epps said. “Actually amending the Constitution would provide greater protection, and it would really change the document.”

‘It’s about the American people’

Lawmakers have talked recently about expanding or restricting the expansion of the Supreme Court with a constitutional amendment. Others have called for an amendment to clarify whether campaign donations are a protected form of free speech – or to add a constitutional right to clean air and water.

But history reveals a 27-in-11,000 chance of success.

Feldman doesn’t expect any new proposals to be successful because of hyper partisanship at both the federal and state levels.

“The founders intended the process to be difficult, and it is difficult,” Feldman said. “And it’s more difficult now than it used to be simply because our politics are more fractured now than they used to be.”

Epps has a different view. “In order to assess whether an amendment is possible, you can’t just look at Congress as it is. Because amending the Constitution is a long process.” These processes take years, even decades, and any given amendment will likely outlast the Congress that introduces it.

“And arguably, that’s not bad,” Epps said. “You don’t want a system where one party could get access to legislative power on one occasion and changed the fundamental rules of the game.”

And even unsuccessful amendments like the stalled ERA can influence legislation and impact judicial decisions because of public attention and involvement.

“The Constitution’s not about Congress. The Constitution’s certainly not about the Supreme Court,” Epps said. “It’s about the American people. We, the people of the United States.”