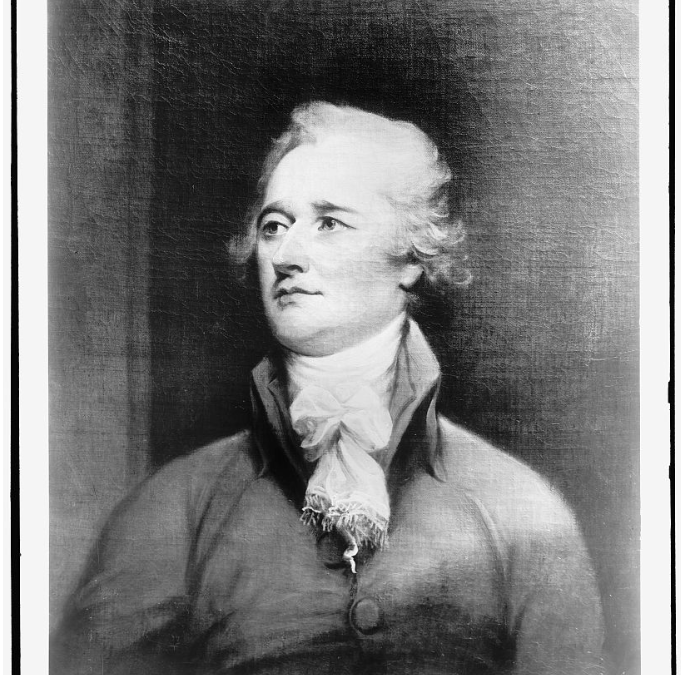

We the People: After some linguistic detective work, it became more clear that Alexander Hamilton was the most prolific Federalist Papers author

Each week, The Spokesman-Review examines one question from the Naturalization Test immigrants must pass to become United States citizens.

Today’s question: The Federalist Papers supported the passage of the U.S. Constitution – Name one of the writers.

In the late 1780s, a few years after the U.S. won its independence and shortly following the Constitutional Convention, three of the new country’s founding fathers published a series of essays urging the ratification of the new U.S. Constitution.

The essays, called the Federalist Papers, were originally intended as opinion pieces to persuade the public to trust the proposed balance between state and federal powers.

“A big part of the Federalist Papers was trying to reassure people that this new federal government wouldn’t actually be all that powerful and all that scary and dangerous,” said Joseph Hoffmann, a professor at Indiana University’s Maurer School of Law and a former clerk for Supreme Court Justice William Rehnquist. He taught a 12-lecture series on the Federalist Papers for the online learning platform The Great Courses.

“As time went by, it became clear that the Federalist Papers were also really a kind of explanation of how the Constitution was supposed to work.”

In fact, the Supreme Court still cites the essays’ arguments as the justices interpret the limits of the Constitution and the balance of powers in the U.S.

“It’s the best document we have to explain what the people who wrote the Constitution believed it was, you know, how it should be read and interpreted and applied,” Hoffmann said. “It’s kind of the bible of the Constitution, in a way – or the textbook, the instruction manual for the Constitution.”

The 85 essays of the Federalist Papers found pop culture fame after the 2015 Broadway debut of the musical “Hamilton,” written by Lin-Manuel Miranda. The show premieres in Spokane this week at the First Interstate Center for the Arts.

“John Jay got sick after writing five. James Madison wrote 29. Hamilton wrote the other 51!” sings Aaron Burr in spiteful admiration of Hamilton at the end of the play’s first act.

“There’s no question that Hamilton was the driving force behind the whole thing,” Hoffmann said. “He was the one who had the sense that this kind of PR thing needed to happen if the Constitution was going to get ratified.”

But the authorship attribution to Jay, Madison and Hamilton was a later discovery. The Federalist Papers were initially published throughout 1787-88 as individual essays in colonial newspapers under the trio’s collective pen name “Publius,” a reference to an ancient Roman statesman who championed equality and the republic.

The public generally understood Jay, Madison and Hamilton to have been behind “Publius,” but the individual essays weren’t differentiated by author at the time of publication – and the essays were only later assembled together into the “The Federalist Papers” collection.

For that reason, the Federalist Papers’ authorship has long been debated, Hoffmann said. Historians’ analysis was helped in most cases by the authors claiming their essays after the fact – but about a dozen of the essays were claimed by both Hamilton and Madison.

To determine authorship of the disputed essays, statisticians Frederick Mosteller and David Wallace performed an experiment in the 1960s that examined the linguistic choices in each of the essays.

The clues were small: One founder opted for “while” and another preferred “whilst,” explained Patrick Juola, a forensic linguist and professor of computer science at Duquesne University, originally from the Pacific Northwest. In 2013, Juola’s linguistic analysis of the Robert Galbraith book “The Cuckoo’s Calling” broke the news that Galbraith was a pseudonym for Harry Potter author J.K. Rowling.

“Nobody uses the same words; nobody uses the same grammar. Everyone has a slightly, little, slightly different way of expressing themselves, which we can formally call an idiolect – but less formally, we could just call style. And so by looking at the style, we can try and figure out who wrote the document.”

Spokane locals might say “soda,” while others would call the same thing “pop,” Juola said. That’s a regional clue – but then there are just individual inclinations, of which the writer may not even be aware. For example, Juola said, do you set your fork “to the right,” “on the right” or “at the right” of your plate at the table?

“We look for little cues to authorship based on how people write in one instance, and we see if we can find those cues to how they write in an instance of a document where we don’t know, and they’re trying to figure out who wrote it,” Juola said.

Mosteller and Wallace found a few dozen of these small but significant style clues, locking in what became the general consensus that matches Miranda’s breakdown in the Broadway line: five by Jay, 29 by Madison and the other 51 by Hamilton.

“At this point, I’d be willing to say that we know who wrote the Federalist Papers,” Juola said. “But anytime somebody proposes a new method or wants to try and improve the technology or something like that, it’s the first problem that he or she looks at… because if you have a new method, and it won’t give you an answer for the Federalist Papers, it’s not a very good new method.”